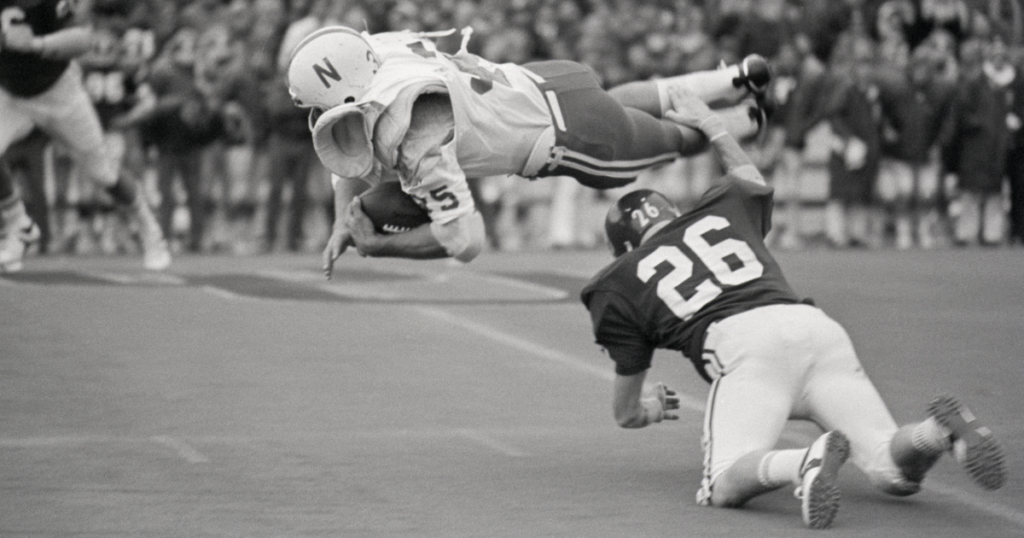

Epic Nebraska-Oklahoma game in 1971 points to incredible evolution in college football TV coverage

With his razor-sharp recall, 89-year-old Chuck Neinas this week found the old program from the 1971 Nebraska-Oklahoma classic in his Boulder, Colo., home and became lost in nostalgia. After all these years, the man who was Big Eight Conference commissioner 50 years ago still considers it the Game of the Century.

The iconic matchup finds renewed relevance this week with Oklahoma hosting Nebraska. Stirring half-century-old memories crystalizes the extraordinary evolution in TV coverage the sport has undergone in the past 50 years. Revisiting that unforgettable game also highlights how a confluence of factors led to it becoming the most-watched college football game in history at the time.

Consider that 55 million viewers watched No. 1 Nebraska beat No. 2 Oklahoma 35-31 that Thanksgiving Day. And also consider that the United States’ population was around 207 million and that there were only 65 million households nationwide. When comparing it to today, Neinas said the audience reflected Super Bowl-level viewership.

“One out of four people watched it,” Neinas told On3. “And you never measure what the audience is in the bars. The build-up to the game was exceptional because these two teams were so superior to anyone else in the country.”

Both were undefeated. Oklahoma averaged 45 points per game, while Nebraska, the defending national champion, allowed only six points per game. Sports Illustrated’s cover aptly dubbed the clash “Irresistible Oklahoma meets immovable Nebraska.”

It was a different sports ecosystem 50 years ago. There were no multibillion-dollar media rights deals. Before social media, satellite TV and cable, before every college football game of consequence was on TV and every score update available (with highlights) within seconds on a mobile device, there was a dearth of televised games. Even for top teams.

The book, “The Game of the Century: Nebraska vs. Oklahoma in College Football’s Ultimate Battle,” points out that despite its national prowess, Nebraska had just two televised games on its 1971 schedule — Colorado on October 30 and Oklahoma on November 25. Both were the national game of the week on ABC.

At the time, Neinas said, NCAA policy stipulated that teams were only allowed a limited number of TV appearances over a two-year period. Starved for national exposure, the Big Eight hired Neinas in large part to help garner national relevance. With the ’71 game, mission accomplished.

The NFL wasn’t the NFL

The other factor that contributed to the ’71 game captivating the nation on Thanksgiving Day was that the NFL was not the behemoth it has become. The NFL was only a few years removed from the NFL-AFL merger and the Super Bowl was just 5 years old; that event still was maturing into a cultural spectacle. While there were two NFL games televised that Thanksgiving—Kansas City at Detroit on NBC and the Los Angeles Rams at Dallas on CBS — all eyes were on the college football game on ABC. The appetite to see two teams that had been on a collision course all season was insatiable.

The powerful voice of Howard Cosell hyped the Nebraska-Oklahoma game during the Monday Night Football game three days before Thanksgiving. Stores in Nebraska and Oklahoma ran large newspaper ads urging consumers to buy a new TV set so this one game could be viewed in color. Governors and senators from the two states declared “Beat the other team” days.

As large as the TV audience was, ABC actually predicted 80 million viewers in the United States, with network publicist Beano Cook proclaiming, “We’ll eat the pros alive. This will be one of the most-watched games of all time.”

“The Game of the Century” said Western Union delivered the game live and in color via satellite to four feed lines in the Pacific that served Alaska, Hawaii, Korea and the Philippines. In the Atlantic, three feed lines served Germany, Panama and Puerto Rico.

As for media attention, 97 writers covered the game, representing, among others, 65 newspapers, Sports Illustrated and Newsweek; some requests were denied because OU ran out of room in the press box.

The morning of the game, Neinas’ assistant, Mickey Holmes, told him that legendary sportswriter Dan Jenkins “wants to come in for the game. Would you give up your seat in the press box to Dan Jenkins?”

Neinas: “Hell, yes.”

Nebraska assistant remembers build-up

One thing hasn’t changed: The build-up was stressful for players and coaches. Jim Walden, the Nebraska linebackers coach in 1971, told On3’s Ivan Maisel that it was a 12-day “ordeal” from the time the Huskers played their last game (a 44-17 win at Kansas State) until Thanksgiving.

“I’d hang out down with the defensive guys. The first four or five days you think, ‘Aw, hell, we’re going to kill these guys. We can stop that wishbone,’ ” Walden said. “About the last two days, you’re going, ‘Oh, shit. They’re going to score 50 points.’ Your mind is just blowing up.

“We were confident but nervous. The biggest thing was to get it going because it had been (12) days of constant 1 vs. 2, media pounding us, interviews. You were just so ready to play the game. There was such a great relief to get on the plane, fly to Norman, let’s get this thing going. It seems like it took forever. That’s the biggest thing I came away with.”

Anxiety was plentiful with the Sooners, as well. The day before the game, Oklahoma defensive line coach Jimmy Johnson — yes, the one who went on to win a national title at the University of Miami and two Super Bowls with the Dallas Cowboys — changed his routine. Instead of talking to the unit as a group, he chose to talk with each player individually, reminding each of his assignments. When it was his time to talk with Johnson, Oklahoma’s Lucious Selmon recalled in the book, “I had a fever, and I know I wasn’t sick. I was so nervous I gave myself a fever.”

Nebraska, meanwhile, was so paranoid about possible malfeasance by folks in Norman that they brought in their own food to avoid any chance of food poisoning.

Other games before this “Game of the Century” also attracted considerable hype, most notably Michigan State-Notre Dame in 1966 (which ended in a tie) and Arkansas-Texas in 1969 (which ended with Texas scoring late for a one-point win). But Neinas said Nebraska-Oklahoma exceeded the hype, with Nebraska winning thanks to a TD with 1:38 left.

Among all the details he remembers is just how well the game was played: There were just two penalties (both for 5 yards), and players had such respect for their opponents that they helped them up off the ground.

Chris Schenkel did the play-by-play for ABC, with former Oklahoma coach Bud Wilkinson providing color analysis. Wilkinson later said, “I don’t think there has ever been a college game with as many great players on the field.” While comparing great teams from different eras is challenging, Neinas acknowledged, “It’s tough to think anybody was better than that Nebraska team,” which went on to dominate Alabama in the Orange Bowl 38-6 to capture a second consecutive national title.

ESPN, in its College Football 150 celebration in 2019, named Nebraska-Oklahoma the greatest game ever. The network named the ’71 Huskers the greatest team ever.

Since the game, there has been intense build-up for other No. 1 vs. No. 2 games that were classics. Among them: When No. 1 Florida State visited No. 2 Notre Dame in 1993, it marked the first time ESPN College GameDay went on the road. The game also matched the hype, with the Seminoles falling just short in seven-point loss. The 1991 game between No, 1 Florida State and No. 2 Miami forever will be remembered as “Wide Right I,” the first installment of the Seminoles being cursed by missed late-game field goals. In 1996, No. 1 Florida played at No. 2 Florida State in the last weekend of the regular season. And in 2006, No. 1 Ohio State played No. 2 Michigan to close the regular season for both teams.

The phrase “Game of the Century” since has been put to rest for regular-season matchups because of the introduction of the College Football Playoff in 2014.

In Neinas’ eyes, there was only one anyway. It made the Big Eight Conference, in his view. Kicked off under overcast skies, in 49-degree weather, far more than the 61,826 in attendance have undoubtedly claimed they were at Memorial Stadium to witness it.

“That game,” Neinas said, “lives in history.”

Quick hits

+ Reverberations continue after Notre Dame’s 32-29 nail-biter against Toledo last Saturday was relegated to Peacock, NBCUniversal’s streaming service. Some consumers who subscribed complained on Twitter about latency issues. Latency is the time lag between when a moment is captured and when it is displayed; it varies between several seconds to a few minutes, depending on the technology and device. It’s one of the biggest issues confronting streaming technology in a world increasingly embracing mobile sports betting. Industry sources say sub-half-second latency is required to maintain integrity once in-game sports betting becomes more popular. Whether it’s for entertainment or betting purposes, you can’t have the streaming feed be one play (or more) behind what is occurring in real time in the stadium. Most streaming services haven’t solved the latency issue. But they need to.

+ The other question continues to be when, not if, premium live sports content will migrate from linear networks to streaming services. It’s coming, but not anytime soon is the consensus. That said, change is afoot. At the end of 2020, only about 60 percent of occupied U.S. households paid for TV subscriptions, the lowest level in nearly 30 years, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported. At the same time, consumers are spending more money on streaming; they will spend nearly $50 billion on new video subscription services this year, with an expected rise to $76 billion in 2024, when it is anticipated that spending will surpass traditional TV. When asked how soon to expect top live sports events to move exclusively to streaming, John Kosner, a former longtime ESPN Digital executive who invests in and advises a portfolio of tech start-ups, told On3, “I do expect that you will see more and more games move to streaming — the entire sports media industry is in transition this decade. However, I view last weekend’s Notre Dame standalone offering as experimental. More success will come with full or practically full seasons of content made available for fans to buy on streaming. One-time events risk annoying fans rather than getting them to sign up . . . and stay signed up.”

+ Considering Clay Helton’s firing at USC after just two games, Fox college football analyst Joel Klatt is on point with his tweet that “the vacancy at this point of the season is going to result in between $50 (million)-$75 million in extension money for other schools.” In other words, the mere possibility that their coach may be tempted by the marquee opening could force schools like Oregon, Cincinnati and Penn State to give their coaches lucrative extensions.

+ TCU coach Gary Patterson, not one to mince words, spoke the truth when he offered the quote of the week to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram regarding some schools using NIL as a recruiting tool, which technically is an NCAA violation: “There’s five SEC schools calling (a current unnamed TCU player) and telling him, ‘Here’s what we will give you if you come here and not stay at TCU.’ At the end of the day, that’s just real life. If we don’t do anything about it, within a year we lose him. The rules have changed. There is no wrong anymore.”