The end of an era: Jim Nantz says, ‘Goodbye, Friends’

A distinguished tenure that began on an historic Saturday night in Indianapolis 32 years ago will culminate Monday night in his beloved city of Houston.

If you’re a college basketball fan under 45, Jim Nantz is the play-by-play voice that has escorted you through the most indelible Final Four moments of the past three-plus decades. From Duke’s upset of unbeaten UNLV to Mario Chalmers’ game-tying three-pointer to Kris Jenkins’ national title-winning buzzer-beater, Nantz has been the one constant, the one fixture through the decades, especially as the rest of the sport has undergone such dramatic change.

That will end Monday night, when Nantz calls the final national championship of his venerable career for CBS. On longevity alone, his legacy as the leading voice for a tentpole sporting event for 32 years is unlikely to ever be duplicated.

To appreciate Nantz’s run, consider the three broadcasters who preceded him as the Final Four’s play-by-play man in the sport’s relatively modern era: Brent Musburger, six years at CBS; Gary Bender, three years at CBS; and Dick Enberg, six years at NBC. Spanning the terms of six U.S. presidents, Nantz’s Final Four tenure began when the Internet was a mere rumor and if a highlight was said to go “viral” it would have left everyone dumbfounded.

“It does seem unlikely that any single individual will have a function [like Nantz], going 20, 30 years in one place, doing one thing,” former CBS Sports president Neal Pilson, Nantz’s boss through the 1980s and much of the ‘90s, told On3. “Jim has been a part of the growth of the sport. Would it have done well without him? Sure. But did it do exceptionally well with Jim? Absolutely.”

Monday’s final will be Nantz’s 354th tournament game

When one team cuts down the nets inside NRG Stadium on Monday night, Nantz – who turns 64 in May – will cap a remarkable March Madness broadcasting career: 37 NCAA tournaments, 96 Final Four games, 32 title games and 354 NCAA tournament games. Nantz isn’t retiring. He will maintain his leading role with golf on CBS (most prominently calling the Masters) as well as his pairing with Tony Romo as the network’s top NFL team. Between those sports, he still will be on the road 38 out of 52 weekends. He plans on calling the NFL at least through 2033, the final year of CBS’ contract with the league.

The grind of March Madness, something near and dear to his heart, simply became too much with a 7-year-old son and 9-year-old daughter at home. He plans to spend more time with his family.

Stepping away from college basketball has been something Nantz has considered for at least a few years. He initially targeted 2021 in Indianapolis as his potential swan song. It offered great symmetry, calling the Final Four beside analyst Grant Hill (as well as analyst Bill Raftery) in the same city where Nantz called Hill’s famous one-handed alley-oop dunk in his first title game as play-by-play man 30 years before. But he didn’t want his last dance, so to speak, to be so significantly impacted by the pandemic, which forced the NCAA to stage the tournament in a bubble-like setting in Indianapolis.

Nantz will hand the baton to a familiar voice – Ian Eagle. There are no indications that Eagle won’t team with Raftery; the tandem had terrific chemistry when they broadcast then-New Jersey Nets games decades ago. Nor are there signs that Hill won’t be back as an in-game analyst.

“I’ve loved it, and it has been so much fun,” Nantz said on a conference call with reporters. “Something had to go, though. You’re never going to walk away from the NFL – it’s too big – and golf is deep in my heart. It has been an amazing ride and a glorious part of my life.”

Houston is the perfect finale for Nantz. He’s a proud University of Houston alum whose entrance into the profession came from hosting “The Guy Lewis Show,” which ran on the local NBC affiliate. In 1983, he rode the bus with Lewis and Phi Slama Jama to The Pit in Albuquerque for the national title game. With neither a credential nor a ticket, Nantz leaned on a mentor, Matt Musil of KHOU-TV, to sneak him into the arena.

“We were there to see our hearts broken,” Nantz recently told Musil in an interview, referencing North Carolina State’s titanic upset of his Cougars.

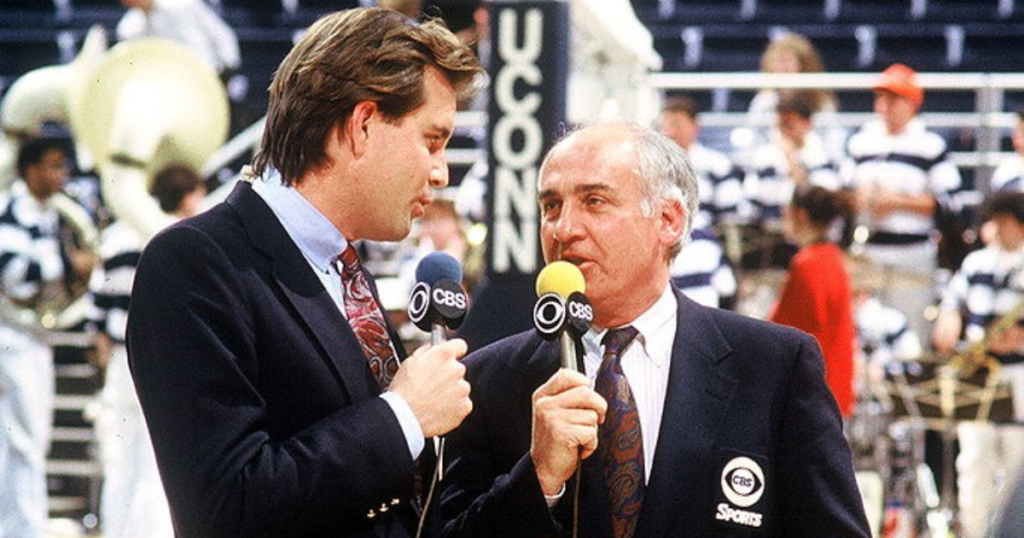

It proved a pivotal moment for Nantz. As he told Musil, before the game he made a beeline for the CBS studio set in the corner of the arena, looking up in awe at Musburger. Three years later at the Final Four in Dallas, it was Nantz hosting that in-venue studio show for CBS, a role he held through the 1990 Final Four. Even then, Pilson saw in Nantz someone who could eventually replace Musburger as the lead Final Four play-by-play voice. Pilson noted early on that “Jim spoke with his audience, not to his audience.”

Raftery recalled calling some games with Nantz early in Nantz’s CBS days and being “enriched by his knowledge and his love of the sport.” And while only in high school, Hill remembers Nantz from those days as well, as he watched and re-watched Final Four games on Betamax in the late 1980s when Nantz was studio host. “When you looked over and saw Jim Nantz,” Hill said, “you knew it was big.”

‘He was at that level when he began’

But that was only the beginning – and before Nantz’s promotion occurred under unusual circumstances. It was April 1, 1990, when Nantz, in Denver for the Final Four, received a peculiar phone call that he was sure was a “tasteless” April Fools’ Day prank, as he said in his autobiography. Was Musburger, the $2 million face of the network, really on his way out of CBS? Yeah, right.

Meantime, Pilson was at the center of contentious discussions with Musburger’s brother and agent, Todd, stirring drama that far exceeded anything on the court; UNLV thrashed Duke by 30 in that season’s title game. Todd Musburger later told Sports Business Journal that he and Pilson engaged in a “knock-down, drag-out verbal battle that was as fierce as anything I’ve ever done as a lawyer – and I used to do murder cases.”

It was Nantz’s time, and Pilson knew the night of the national title game that Nantz would assume the lead role the following year. Pilson told On3, “Fair chance if we renewed Brent for another two, three, five, eight years, we probably would have lost Jim.”

The drama was all on the court in Nantz’s first Final Four. The ’91 semifinals were so rich with storylines that North Carolina’s Dean Smith facing his former pupil, Roy Williams and Kansas, was the undercard. Nantz handled everything with measured aplomb, including Smith’s stunning ejection late in the loss to the Jayhawks and Duke’s shocking upset of undefeated UNLV.

Pilson said he’s stumped by a question about how Nantz has improved over the years because “what he did then and what he does now is so natural and so comfortable and so competently prepared and delivered, it’s hard to say he’s really improved. He was at that level when he began.”

We are unlikely to see another like him, serving as the singular face for a marquee event for so long. Not with, as Pilson noted, so many other players in the media landscape jockeying for position and talent. Whereas broadcasting stars chose among three networks decades ago, now cable outlets (Joe Buck goes from Fox to ESPN) and Big Tech companies like Apple and Amazon (Al Michaels arrives from NBC) also are in play. Plus, Pilson said, there’s just a lot more talent spread across the industry.

One thing that’s always stood out about Nantz, Pilson said, was that his on-camera wrap on the Final Four always seemed to fit the moment, capturing the significance of what we just saw. For more than three decades, he’s been our Final Four narrator. And after calling all of those unforgettable moments that have shaped the sport, his sign-off Monday night – in a city that maintains such a special place in his heart – should be especially poignant.

“It is bittersweet,” Hill said. “Our friend, our leader, our mortar, the guy I feel kind of keeps this whole thing together and has done it so eloquently and masterfully and respectfully for so long – it is crazy. It is surreal that it has come to an end.”