The Big 12's defense of uptempo offense

The Big 12 will be moving much faster in 2022 than we saw in 2021. It was a much slower year for the league with many of the best teams in the league (save for Oklahoma State) running slower, more deliberate offenses. There was good reason to be a little skeptical of the “defense runs this league now!” narratives given the lack of offensive-minded coaches who had quarterbacks and teams they felt comfortable unleashing in aggressive offenses.

We’ll be moving back to the league’s norm in 2022 with the addition of Graham Harrell, Jeff Lebby, Zach Kittley, and Collin Klein into the offensive coordinator roles around the league.

There’s been an argument the league’s decrease in offensive pace and explosiveness was related to the emergence of better defenses around the league, but the proof will be in the pudding now we’ve had a fresh infusion of HUNH (hurry-up, no-huddle) spread offensive minds. What is the nature of this back and forth between uptempo offenses and the league’s defenses? What are these coaches trying to do and what’s been the response from the league’s defenses in recent seasons?

Why the HUNH spread? Why go fast?

There’s a lot of reasons teams like to use tempo and go fast on offense.

Here’s one of the most basic. If your best players are on offense and the best way for you to dictate the outcome of a game is by scoring on offense, then you want to create as many chances as possible for your best players to make game changing plays. You do that by operating with tempo, getting the ball to good players as many times as possible.

There are several other significant factors as well though.

Tempo is very effective at limiting defenses in two significant ways. One, they can’t substitute unless you do. If the offense moves to line up with urgency it drastically limits the defense’s ability to rotate players in and out of the game. If the offense does substitute then by rule the defense must be allowed to do so as well.

Smart tempo coaches like David Yost and Tom Herman would teach their base 11 personnel players to play multiple positions, allowing them to hurry up to the line of scrimmage on 3rd and 8 or 3rd and 2 and have play-calls designed for those specific moments whereas the defense couldn’t sub to a passing downs or short-yardage package. Eliminating defense’s ability to build packages with specific players for specific scenarios can be a big win for HUNH spread offenses. Now the same 11 guys have to be at least competent against EVERYTHING.

In addition to limiting the packaging a defense could do, it also limits how much they can communicate. Either the defense needs to be exceptional at getting calls in from the sideline to all of the defenders before the snap, or else they need to teach their defenders a lot of checks. As in, “if you get this formation, use this front/stunt and this coverage, if you see this formation, you need to change and run this coverage.” It’s hard for fans to appreciate the degree to which this impacts a game, so much is unseen, but it’s a massive factor and particularly against tempo teams.

Tempo makes it hard for the defensive coach to hold his players hands with precise instructions on how to defend the offense, they have to know for themselves what to do and what to expect. This can be a huge advantage for the offense, to contend with the middle linebacker’s football IQ rather than that of the 40-year old millionaire on the sideline. It also requires that defenses have starters on the field at all times who can communicate the right plays to their teammates. Fans who are infuriated by their team opting for slower, more limited veterans over exciting young athletes will see their exasperations grow the more tempo is involved in a game. Not only is it better to play the veteran, but defenses may have to. It’s better to be able to line up and call a defense than to have fast players on the field who can’t even play a defense together.

Many offenses also use tempo to run “check with me” systems. Meaning they’ll hurry to the line of scrimmage, preventing substitutions or lengthy communication from the defensive sideline, but then the offense will stop and look back at their own sideline for instructions. Then they rapidly put those into effect and run the play. If they get the call in fast enough they can allow their own million dollar man offensive coordinator to “hold the chalk last” so to speak with the chance to make the last adjustment. It’s hard for a defensive coordinator to see the adjustment, make his own counter-call, and get it communicated to his players.

If the quarterback can do this without much help from the sideline? Better still. This is why Tom Brady and Peyton Manning are so famous.

Finally, there’s the exhaustion factor. Defenses can’t hold up playing 70+ snaps in a game, they wear down. Particularly up front. 250+ pound frames have a lot of muscle which uses up a great deal of oxygen. If defenses can’t sub in defensive lineman than their main guys will be exhausted by the end of the game. Big guys can’t rush the passer effectively for 60+ snaps a game, they wear down.

The good HUNH spread teams are very comfortable taking games deep into the fourth quarter and winning late when your pass-rush disappears and their quarterback can play pitch and catch for the game-deciding points.

If you do sub in defenders before then to protect the legs of your stars? Well, they’d better be pretty good or you’re just bleeding points and perhaps the offense doesn’t even need the late drives in the fourth quarter to finish you off.

You know what else gets tired out over the course of a game? A defensive gameplan. The main disguises the secondary is using eventually gives way and the offensive coordinator and his quarterback develop a sense of what the defense is trying to do to stop them, then they can adjust and target their opponent with greater precision. The offensive line starts to recognize the blitzes and the run stunts and adjusts. The quarterback sees the coverage disguises and perhaps picks up on tells or else figures out how they want to cover his favorite routes and receivers.

Offense has a lot of advantages against defenses because they dictate the action and determine who goes where. By using space and tempo, those advantages can widen. You force the defense to think hard, act without a lot of direct guidance, and then ultimately beat blocks, cover receivers, and make open field tackles and do so faster and more often.

How do you defend the HUNH spread?

It’s difficult. I’ve seen teams do it well for a spell only to break down late because the offense finally found a hole in the defense or someone got beat in coverage or the defense just got tired.

Modern Big 12 defenses have a few tricks for doing it better than they used to do. One essential trait is being able to either communicate calls quickly to the defenders, or better still, having some base calls the defenders know how to line up and execute without a good deal of oversight from the bench.

Step one in defending the HUNH spread is just being there. Between the tempo, the spacing, and all the nasty run/pass conflicts teams will create for a defender simply to show up in a gap or a passing window is often more resistance than the offense expected to meet. This doesn’t happen without a system for communicating and lining up the defense quickly.

Secondly, HUNH spread defense is probably best accomplished with a true base defense. A team who can put the same 11 players on the field and execute the same main fronts and coverages is better off because then you can incorporate tweaks in the form of gameplan checks rather than specific calls.

Oklahoma found a way to play base defense against the Texas Longhorns in 2018 after getting run over in the regular season matchup in the Red River Shootout when all of their calls and schemes didn’t help their defenders figure out how to fit Texas’ runs or cover their best receivers or just get guys in position to be competitive. Mike Stoops was fired and Ruffin McNeil, who had a great knack for this, took over. He found a starting 11 for the Big 12 Championship game that made them more flexible, they ran a simplified base defense, and he installed a few gameplan checks.

As a general rule, McNeil dared Texas to beat them throwing to Collin Johnson rather than Lil’Jordan Humphrey, always keeping either a nickel corner and/or safety help over Jordan and an extra man in the box against the run. When Texas would load up Johnson and Humphrey both into the boundary, the Sooners would over play them by rolling all three safeties toward the boundary. Then they won the game by having an auto-blitz checked into the game. They knew when Texas audibled the running back to a particular side that they had a play-action pass lined up, so the Sooners would then check their boundary corner into a blitz and have the safety pick up his receiver in man coverage.

OU ran this once or twice but the main one came with the ‘Horns backed up to their end zone on a crucial possession in the fourth quarter. The cornerback came, Texas didn’t see it, and they sacked quarterback Sam Ehlinger in the end zone for a safety.

The key was that McNeil didn’t have to communicate these things in the moment against tempo, he taught the players to do them on the field just as HUNH spread offensive coaches teach their offensive players how to play fast and make live-action tweaks and checks. This is all easier if if you have a flexible base defense installed which the players know how to execute so well that they also understand how it can be tweaked for key situations.

Dave Aranda’s defense at Baylor operates in this fashion and he teaches his players how to check and adjust their blitzes without needing a call from the sideline to tell them what to do.

Finally there’s increasingly more disguises, best exemplified by the flyover defense.

Iowa State’s 3-3-5 flyover defense with three deep safeties offers some help in combating the HUNH spread by presenting a lot of pre-snap confusion about what they’re up to and then a lot more help by inviting the ball into spaces which the defense then closes shut.

A best practice for defending the HUNH spread, or any team that wants to hurry to the line of scrimmage initially if only then to execute a more plodding pace (i.e., Baylor), is to line up in a static look on defense until late before the snap. In the flyover defense, everything is structured to emphasize this advantage.

Check out the following snaps from Iowa State against Oklahoma State last season.

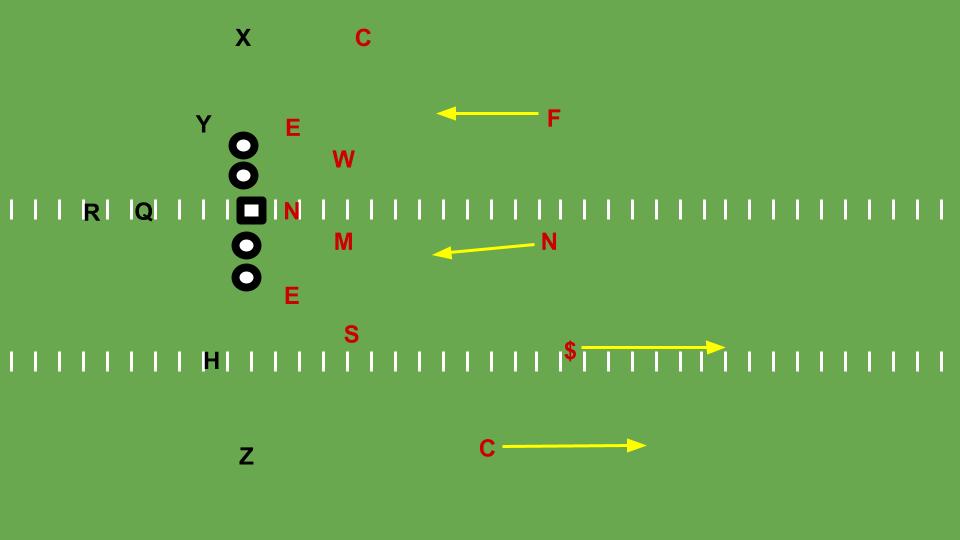

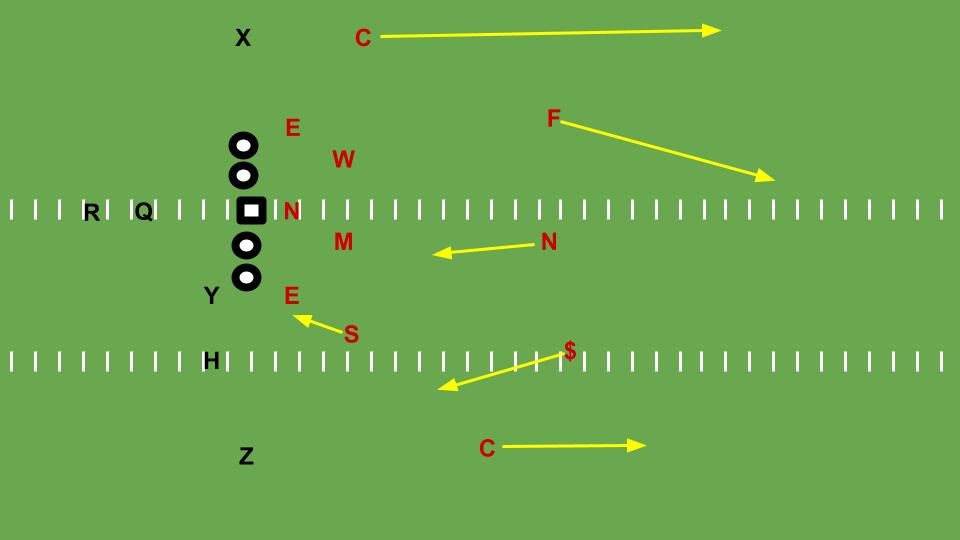

Initially Iowa State is in the 3-3-5 with the slot-side linebacker removed from the box and three deep safeties all lined up around 10 yards deep. Then late before or after the snap, they morph into a different shape.

In the first example Iowa State is playing quarters coverage with the boundary safety both keying the tight end and the nickel (middle safety) reading the quarterback and robbing in the middle. The strong safety outside is playing over the top of the slot to help their Sam linebacker. This is a pretty normal set-up for the Cyclones, presenting a multiple deep-safety look before the snap but giving some of their safeties freedom to aggressively fit downhill against the run.

In example two it’s a similar look before the snap but now it’s a single-high coverage with the boundary safety rotating deep while the strong safety drops down like a nickel on the slot, the Sam linebacker blitzes the edge, and the middle safety plays a hook zone like a linebacker.

It’s not obvious for the offense to tell what the defense will do after the snap. A traditional defense isn’t lined up with so many defenders deep and off the ball, but the Cyclones figured out they can move faster after the snap moving forwards than backwards. So they start deep and then (some at least) move forward.

You can generally count on Iowa State involving some of the safeties and likely the Sam linebacker into the run fit but you can’t be sure of who will do so on a given snap. You also can’t be sure of the specific coverage they’ll play and who will be in what role, it’s all pretty nebulous until they spring into action.

Good HUNH spread defenses do what they can to eliminate the offense’s ability to go into the play easily knowing what play to run to find success in order to keep the pace moving. When the offensive coordinator and quarterback are just running up to the line and rolling through an index of basic plays and reads, you’re dead. When they have to stop and think, you limit their tempo and the gears grind down. When they line up and believe they know what’s happening and then it turns out they don’t? You get negative plays and turnovers.

As the new HUNH spread offensive coordinators take charge across the Big 12, this is the landscape they’ll find waiting for them. A league with much more developed defensive tactics for handling the stress they create. Next we’ll discuss the current shape of the back and forth battle between defenses and this style of offense.

Will the Big 12 remain a more defensive league or will offense strike back in 2022? Discuss for free on the Flyover Football board!