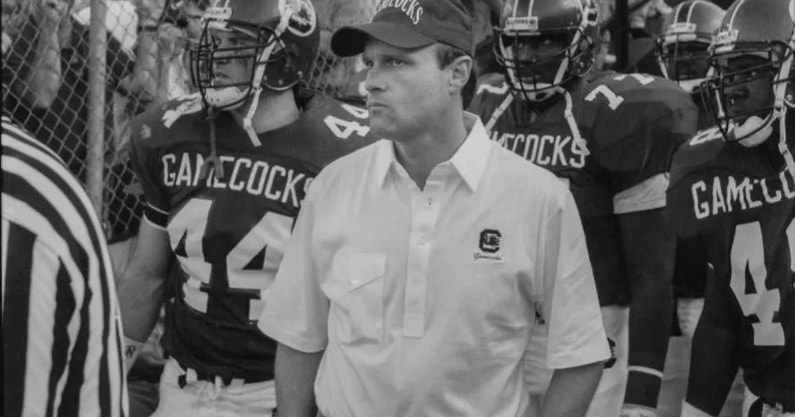

Part II: A conversation with former South Carolina football coach Sparky Woods

Alan Piercy is the author of A Gamecock Odyssey: University of South Carolina Sports in the Independent Era (1971-1991). The following was originally published on Alan’s South By Southeast newsletter.

The second and final installment – Former Gamecock football coach reflects on his time in Columbia and a life in football. Read the first installment here.

It all happened on a balmy Friday afternoon in early September 1992. It was an odd setting at the outset of what would prove to be an exceedingly odd season – the University of South Carolina’s first as a member of an all-sports league since leaving the Atlantic Coast Conference some 21 years prior.

The environs around Williams-Brice Stadium have softened over the years since, thanks to the greening and beautification of Springs Brooks Plaza, leafy residential and tailgating developments nearby, and the verdant Gamecock Village, once the site of an aging and ramshackle state farmer’s market. Stately red brick columns, wrought iron gates, and a budding urban forest of hundreds of trees have replaced the heat-blasted asphalt apron that formerly surrounded the stadium.

A more spartan scene awaited the Gamecocks’ Southeastern Conference debut those many years ago, set as it was amongst an industrial corridor south of campus, replete with machine shops and warehouses and dusty parking lots – the kind of hardscrabble setting that made one ponder if their tetanus vaccine was current.

Against this gritty backdrop that September day appeared Archibald Thibeaux, a lanky native of New Orleans and self-proclaimed witch doctor, then residing in Blythewood. With his billowing brown suit, stovepipe hat, and voodoo face paint, Thibeaux certainly looked the part.

As a late summer sun radiated off the hotplate asphalt slab near the west-side stadium gates, a hundred-or-so curious onlookers formed a semi-circle around Thibeaux. They watched as he tossed carefully procured ingredients into a bubbling cauldron – a recipe designed to exorcise the dreaded “Chicken Curse.”

First into the pot was “magic dust,” or perhaps ashes from Thibeaux’s fireplace, mused The State’s David Newton. Then a dash of something green and a pinch of something orange, followed by “something black from a jar.” Finally, a dramatic flurry of (what else?) chicken feathers.

Smoke billowed from the cauldron as those in attendance, more familiar with Methodists than mystics, stood with uncomprehending gazes, arms crossed, hands on hips, not quite sure what to make of the bizarre spectacle.

“Back to where you belong!” Thibeaux chanted, his long arms extended, fingers splayed dramatically, imploring the removal of that bedeviling spirit. “Chicken Curse be gone!”

With that, the ceremony ended as bewildered attendees filtered haltingly back to their cars, unsure exactly what they had witnessed.

Pulling into Columbia about that time was the No. 14-ranked Georgia Bulldogs for the next day’s gridiron spectacle, and the Gamecocks’ SEC debut.

SEC play kicks off

It started promisingly enough on that balmy first Saturday evening of September 1992. A record crowd of 75,060 fans gathered under cloudy skies to witness for the first time the pomp and ceremony of Southeastern Conference football at Williams-Brice Stadium.

The Carolina Marching Band, newly christened “The Mighty Sound of the Southeast,” played with extra panache. A crew of parachutists delivered the game ball to midfield. A commemorative coin was used for the opening toss. Flags representing each SEC school fluttered from the end-zone stands. The playing field sported a special logo in recognition of the program’s 100th season. Adding to the hoopla, a historic border rivalry was about to be renewed as the University of South Carolina kicked off its first conference football game in twenty years.

The anticipation crescendoed just before kickoff, as the theme from “2001 – A Space Odyssey” blared from stadium speakers and fingers of heat lightning lit the western horizon. As the final strains of “2001” sent the record crowd into a frenzy, the Gamecocks burst from the southwest tunnel of the stadium, through the human tunnel of the Carolina Band, sporting all-black uniforms for the first time since 1988.

Heightening the anticipation that something special might be brewing, Carolina played shutout defense in the first half, forcing two fumbles, while two Marty Simpson field goals paced the Gamecocks to a 6-0 halftime lead.

That was the high-water mark of Carolina football for the evening, and for some weeks to come. Georgia’s Garrison Hearst rumbled for a 49-yard touchdown on the third play from scrimmage after the half, and the Bulldogs took a lead they would not relinquish. The previously sleepwalking Bulldogs dominated the second half, winning 28-6.

A spirited loss to a powerful Georgia team in week one was no great surprise, and followed the script of many games in that rivalry dating back to 1894.

Things turned dire in week two, however, with a humiliating 45-7 loss to fellow SEC rookie program, Arkansas. Compounding matters, the Razorbacks had suffered an embarrassing 10-3 defeat at home to none other than The Citadel in week one, a loss which cost Arkansas coach Jack Crowe his job. During halftime, the Gamecocks down 31-0, fans directed their considerable ire toward athletics director King Dixon. Boos rained down during an unfortunately timed on-field recognition as part of the season-long 100-year celebration.

The season continued to spiral over the following three weeks, with a gloomy home loss to East Carolina and road losses to Kentucky and No. 9 Alabama. Ahead of the game in Tuscaloosa, embattled senior quarterback Wright Mitchell quit the team after being benched in favor of redshirt freshman Blake Williamson.

Entering an open date, which the understated Woods called “much needed,” Carolina found its season in deep peril. The Gamecocks not only stood at 0-5, but also owned Division I football’s longest losing streak at nine games, going back to November of 1991. They were the only winless team in the SEC by mid-October, and found themselves last in nearly every statistical category, having been outscored by opponents 154-47. Adding to that, Jackie Sherrill’s 15th-ranked Mississippi State squad was slated to visit Columbia for an Oct. 17 matchup in game six.

Following the open date weekend, things took a turn for the surreal. In a players-only meeting on Monday, Oct. 12, the team reportedly voted 62 to 24 to ask Woods to resign. Woods, reached that evening for comment by Columbia television station WOLO-TV said he had no intention of stepping aside.

“No. I came here and worked very hard. Our staffs worked very hard,” Woods said. “We’re working as a team. A team does everything together. We’re not 0-5 because of any individual’s fault. It’s all our problems, and we’ve all got to be a solution to the problem.”

Athletics director King Dixon declined comment, deferring to Woods, adding, “that’s a football matter… I just don’t think it would be appropriate as athletics director to comment on that at this particular time.”

By Tuesday afternoon, Woods had engineered an uneasy truce with his team and had them back on the practice field. This followed a vote of confidence from Dixon, who by Tuesday morning voiced support for his head coach. A pre-practice locker room visit by USC President John Palms further solidified Woods’ standing.

There even seemed to be some question as to the extent of the revolt. Senior linebacker Ben Hogan told David Newton of The State that the player’s only meeting was called by “a few guys who had complaints… guys who thought they should be playing more, guys who had been moved from first team to second team.” Hogan elaborated, “Most of us didn’t even know we were having a meeting. There was no organization to it. I was standing in the locker room in my jock strap and somebody called a team meeting out. I thought Coach Woods might have called it.”

Reflecting back on the situation now, Woods says handling the crisis was one of his better coaching moments.

“I said [to the team] ‘I want you, we need everybody here. I want everybody to come back and we’re gonna turn this around. We’re gonna beat Mississippi State.’ I said, ‘However, I will tell you this – we’re gonna practice here at 7 o’clock, and I hope every one of you comes back, but if you don’t, we will take up your stuff and we’re gonna move on without you.’”

Everyone did come back, and looking for a spark, Woods named freshman Steve Taneyhill starting quarterback for the Mississippi State game.

Taneyhill is a Gamecock legend now, but in October of 1992, he was a relatively untested, though brash true freshman from Altoona, Pa. His arrival in Columbia caused a stir from the beginning, wearing long hair and festooned with an earring stud – far from a standard look in the sleepy Southern college town that was Columbia in those days. He exuded confidence, boasting to reporters during spring practice that he would be the starting quarterback by mid-season. That boast and his cocky persona did little to endear him to teammates early on.

Still, Woods was ready to try his hand with a new quarterback. It represented a fresh start, and an injection of confidence was exactly what his team needed. When the Gamecocks took the field to the strains of “2001” on that gorgeous October afternoon against the 15th-ranked Mississippi State Bulldogs, they did so with their third starting quarterback in six games, and a true freshman at that.

The 19-year-old Taneyhill enjoyed one of the most Taneyhill of days that Saturday, completing 7 of 14 passes for 183 yards and two touchdowns, while guiding the Gamecocks to a season-best 505 total yards and an unlikely 21-6 upset win over a top-15 conference team. Beyond the stats, though, he injected a desperately needed element of swagger to a previously beleaguered Gamecock team.

The State’s Bob Gillespie wrote of Taneyhill’s antics,

“He played to the crowd like a cheerleader, bouncing around on the sidelines, waving a towel at the fans, cupping a hand to his ear as if to say, ‘Louder, I can’t hear you!’ Is there enough mustard at the concession stands to cover this guy?”

Before 55,102 fans, the smallest home crowd of the season, a legend was born. Had Taneyhill faded into oblivion after that game (as if he were ever capable of such a thing), he would still be revered at Carolina for the excitement and joy he brought to Gamecock Nation that fall afternoon in the unlikeliest of scenarios. He would still enjoy legend status for snapping the nation’s longest losing streak, for quarterbacking the program’s first SEC win, for enabling smiles to once again enliven the faces of players and coaches and fans alike.

Top 10

- 1New

Behind Enemy Lines

The A&M perspective

- 2Hot

🏀 Four-star PG COMMITS!

MBB lands big pledge!

- 3

Starter added to injury report

Thursday update

- 4

Mailbag: Sellers, Stewart, OC, NIL

Chris Clark answers your questions

- 5Hot

Injury report analysis

South Carolina looks healthy heading into Texas A&M

Get the Daily On3 Newsletter in your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

But of course, he was not done. Behind Taneyhill’s heroics and Woods’ steady leadership, Carolina surged to five victories over their final six games, defeating Vanderbilt, winning a home thriller over No. 16-ranked Tennessee, dispatching Louisiana Tech, and securing a cathartic win at Clemson – the first since 1984 – in a season finale worthy of a chef’s kiss. In their one late-season loss, a 14-9 setback against No. 11 Florida in Gainesville, the Gamecocks played valiantly, led at the half, and came oh-so-close to six-straight wins and bowl eligibility. After the 0-5 start, it was an astounding turnaround, and one of the feel-good stories of the 1992 college football season.

Elation, then deflation in ‘93

Woods’ final season in Columbia started with one of the most unforgettable game-ending plays in program history. Brandon Bennett’s thrilling last-second dive over the Bulldog goal line gave the Gamecocks a dramatic and improbable 23-21 road win over No. 14 Georgia. Former Georgia and South Carolina radio legends, Larry Munson and Bob Fulton, respectively, called the iconic play in their own distinctive styles, (a highlight is color analyst Tommy Suggs’ wild emotional euphoria in contrast with Fulton’s cool, professional delivery).

Any Gamecock fan old enough to remember will tell you exactly where they were when it happened – it was that kind of moment.

The State’s Bob Spear called it the biggest win in program history. And it felt that way on the heels of Carolina’s 5-1 finish to 1992, followed by an offseason of good feelings and exuberant optimism. It felt as if the Gamecocks had arrived despite the low preseason expectations from league pundits.

Spear continued,

“They are, after all, the new guys in the Southeastern Conference, commoners in Camelot, an afterthought for membership, invited only in the aftermath of Florida State’s refusal, the subject of the know-it-all’s poison pens. No players on the SEC’s preseason all-star team. No chance in the SEC’s Eastern Division. No prayer at Georgia. Show us something, the SEC said. They did Saturday. South Carolina 23, Georgia 21. Hello, SEC, the Gamecocks said. We can play too.”

The golden glow from Athens was short-lived, however, as Carolina stumbled to a 3-7 finish the rest of the way. The losses were mostly respectable, including a one-point road loss at Arkansas, and a valiant effort at home versus defending national champion and No. 2-ranked Alabama. There were ugly losses too, in a 23-0 defeat at Mississippi State, and a 55-3 embarrassment at No. 3 Tennessee late in the season.

By 1993, Mike McGee had replaced King Dixon as athletics director. The regime change left Woods vulnerable, and USC’s third-straight losing season ultimately cost him his job.

“I don’t live in the past,” Woods reflects now, “I try to live in the future. I realize this business is hard. Most of my memories about South Carolina are fond memories. But… when they brought Mike in there, he had a plan and it didn’t include me.”

Woods noted he was slow to respond to me about this interview, careful not to speak ill of McGee, South Carolina’s athletics director from 1993-2005, who died in 2019. Still, the sting of 1993 is evident in Woods’ recollections of the time.

“I’ve been fired. I get this business. We had a plan. I saw all those facilities because King [Dixon] and I sat down and drew them out long before they were built. We just never had a chance to build them while I was there,” says Woods, referring to stadium and facilities improvements that ultimately came to fruition after his departure.

“They took a [local news viewer’s] poll about whether to retain me, and I thought the poll would be really lopsided to fire me. Well, it wasn’t. Most people voted to give [me] another year, and I think it scared Mike, because Mike came in there to fix it, and he couldn’t fix it if I was there. If we won, I would get the credit. I thought we were gonna do some good things.”

Woods’ assertion that better days lay ahead for the Gamecock program is validated to a degree by the 1994 season. The five-season tenure of his successor, Brad Scott, ended in a disastrous 1-10 season in 1998, which led in turn to the infamous 0-21 streak running the entirety of Lou Holtz’s first season in 1999. But in Scott’s first season at Carolina, the Gamecocks went 7-5, including a 33-7 thrashing of Clemson. Moreover, the ‘93 squad secured the school’s first-ever bowl win – a 24-21 triumph over West Virginia (along with a passel of demons from the program’s previous 0-8 bowl record) in the Carquest Bowl. This, with a roster full of Sparky Woods’ recruits.

Might Woods have won that first bowl game in 1994 given a reprieve? Or perhaps as early as 1989, or 1990, had his program been allowed to accept post-season bids? Would a bowl win, or perhaps as many as three, have changed the storyline of Woods’ tenure at South Carolina? Inarguably, it would have.

Woods certainly achieved his mission of stabilizing the USC program in the aftermath of the Morrison years. He brought unquestionable integrity to his role, guiding the program with a steady hand through its baptism by fire in the Southeastern Conference, and set the stage for future success. His handling of the player revolt and subsequent turnaround in 1992 remains a master class in leadership and crisis management.

Ultimately, what Woods told reporters following the news of his dismissal as USC’s head coach on Nov. 29, 1993, probably still best summarizes his views on the matter today. “The [USC football] program is in a lot better shape than it was when I arrived. I have no regrets, but only disappointment that I am not able to complete what I started.”

Still, a treasure trove of memories

Woods recalls telling his son Casey of accepting the job at South Carolina in 1989. The younger Woods, now the offensive coordinator at SMU, was six years old at the time.

“I remember telling him, we’re gonna go to South Carolina. And he looked at me and he said ‘Dad, you mean we’re not gonna be [Appalachian State] Mountaineers anymore?’ And I said well, now, we’ll always be, but I think we can help those players down in South Carolina. So they sent the plane up to get us for the press conference, and he sat up in the front seat next to Joe Baier, the pilot, and as we came in, Joe kind of went over the stadium and Casey looked back around at me and said, ‘That’s a pretty big stadium!’ And he switched [to being a Gamecock] right quick.”

Woods remembers fondly the spring Gamecock Club circuit.

“I think I spoke at forty-one Gamecock Club meetings every spring. Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, I would get off the practice field and get on the airplane and go. I tell you what, I had high blood pressure because of all the barbecue I ate,” Woods laughs, “but it was fun.”

Following his South Carolina exit, Woods spent another two decades in football, making eight stops along the way, including as head coach at Virginia Military Institute from 2008 to 2014. His final stop was at UNC as an advisor to then-head coach Mack Brown from 2019 to 2023. Woods and Brown had known each other since they were both assistant coaches at Iowa State from 1979 to 1981. Woods served as Brown’s offensive coordinator at Appalachian State in 1983, then replaced Brown as the Mountaineers’ head coach in 1984. Relationships run deep in the coaching profession.

Woods still follows the South Carolina program from a distance. He is a fan of Gamecock head coach Shane Beamer and sees some of himself in USC’s current head man.

“I think he’s doing a good job. I think he busts his tail. I remember one year before the season started, I took the entire team all the way up [to the upper deck]. They had never been that high, and they were holding onto each other. But I talked to them about our fans and why, when you go out and play, how important that is. Well, I saw where Coach Beamer did the same thing [in 2022]. There’s so many things that he’s done that reminds me of what we did. He’s doing a good job.”

Woods paused, thinking back over his time at Carolina and the challenges and opportunities Shane Beamer faces today, not altogether dissimilar from his own.

“It’s not an easy job,” Woods said, “but it’s a great, great place.”