Go Rest High on That Mountain

On the morning of November 28, 2009 – the day of the South Carolina-Clemson football game – I was walking my Golden Retriever puppy in Cleveland Park in downtown Greenville, SC.

It was a crisp, sunny autumn day, and I was nervous the way that I am always nervous in the hours before South Carolina plays Clemson. My dog, Jamie, was not nervous. She was bouncing and romping through the park with gleeful abandon, sniffing every blade of grass, investigating every park bench and manhole cover and tree stump, and occasionally stopping to look at me as though she couldn’t quite believe the world was this exciting and wondered if I realized it, too.

Not even five months old at the time, she was still in that glorious roly-poly ball of fur phase that goes by all too quickly, attached to a black leash and a garnet South Carolina Gamecock collar that I had just bought her and that was far too big for her tiny neck. She could escape the collar with ease, and often did. But she was so little then I could catch up to her in two quick strides – she couldn’t get away from me if she tried.

For the first time since my childhood, I had no plans for the rivalry game.

In truth, I wasn’t entirely sure I’d watch it. The Gamecocks had lost three in a row during that grim stretch of the 2009 season, and worse, they’d lost six of their last seven to the Tigers (who were scheduled to play in the ACC Championship game a week later). Did I really need to put myself through it?

Besides, I had a puppy to play with.

I was living at the time in a sleek condo in downtown Greenville that I’d decorated to resemble the ultimate bachelor pad, and I’d bought the dog in one of those bold and half-baked strokes of genius that often come in the middle of the night to single men who are creeping towards middle age. “You know what I like about this place?” a friend of mine asked me when he visited the condo. “There’s not a trace of women in it.” This was the moment I realized maybe the place needed a trace of woman in it.

That’s when I decided to get a female Golden puppy, largely because every Golden I’d ever seen on television or in the movies appeared to be resting snugly in a family compound, the picture of calm, drama-free, looking Christmas card-ready and cozy. Adding a drama-free gal to the pad sounded like a bulletproof plan. I’d already bought a convertible and grown my hair out – this was just the next logical step in the midlife crisis, I thought.

That November morning, after we’d gotten back home, I ended up being unable to resist watching the game after all. I turned on the TV for her, tuned it to the channel where the game would be broadcasting, and headed to a downtown bar to see what happened.

I got to the bar just in time to watch C.J. Spiller return the opening freaking kickoff back for a touchdown as the patrons erupted into Clemson fight songs and cheers. Here we go again. I felt like the loneliest man on planet Earth. Why had I left the puppy for this nonsense?

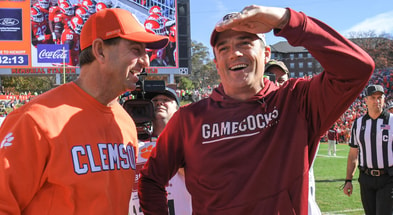

Then something interesting happened. Coach Steve Spurrier inserted cornerback Stephon Gilmore in at quarterback, a position Gilmore hadn’t been playing at the collegiate level. The Tiger defense seemed bewildered by the move, suddenly 12 steps slow and 30 seconds late on every play.

Before long the Gamecocks had reclaimed the momentum, then the lead, and then I was watching despondent Clemson fans fleeing the bar in a dead sprint, and I was looking at a television set that showed a 34-17 final score in favor of South Carolina, and I was hustling back to the condo to see what trouble the little girl had gotten into while I was gone, a manic smile frozen on my face.

I found her in front of the TV, the huge Gamecock collar still drooping off her neck. She’d christened the rug with a Happy Celebration Puddle to commemorate the moment.

Following that 2009 upset, South Carolina won five straight games against their archrivals during the first years of my dog’s life, the longest streak of my lifetime, and I started to believe the wins would last forever as long as she was there, as long as I had her as my own private good-luck charm. Jamie never outgrew that Gamecock collar, and she wore it for the next 13 years.

And she was still wearing it last week, when we said goodbye to her.

Here Comes Trouble

Here’s a true story about my dog.

Any time my wife and I would hug each other, Jamie would scramble out of a reclining position, run over to where we were, hop up on her two hind legs and wrap her front two paws around us both in a group hug. No one ever taught her to do this. It wasn’t a party trick. She just couldn’t stand to be left out.

There were so many things like that, of course, so many of those heart-melting dog moments that you tell stories about, through tear-stained eyes, when the pet is gone. And she had a lot – I mean, a lot – of those maddening traits that leave you firing off a few choice curse words, the kinds of things we’re supposed to remember with wistful fondness once they’ve left us but that in the moment make the veins in our forehead pulse, the kind of “lovable rascal” traits we associate with all those Hallmark movies and sweet-natured dog memoirs.

She waged a years-long campaign against my rugs and furniture. Over the course of a few months, she gnawed one of the legs of my coffee table until she’d whittled it into a perfect toothpick while leaving the other three legs entirely pristine. One night after I collapsed on the couch, she somehow nosed my wallet out of my pants and made a swift decision to chew it to bits, along with my ATM card, then attacked my DVD collection (RIP, “Gangs of New York”). And when Jamie and I moved in with the lovely woman who is now my wife, the dog went right to work on her place, too, ripping up the floor in her downstairs bathroom to announce her presence with authority.

But trying to paint her into that old familiar picture – the charming rogue, the adorable scoundrel – just doesn’t do justice to who she really was.

Jamie was a true eccentric, a genuine oddity on four legs. More than anything, she was like one of those kooky old aunts that you encounter in a 19 th Century British novel, the kind of quirky, talkative, emotional busybody and lifelong Drama Queen who occasionally needs to take to bed for a month to convalesce with the curtains closed in one of the dusty third-floor bedrooms (so much for my dreams of adding a drama-free gal to my life).

She just couldn’t resist being all in your business, at all times and at every moment, and as such, every other dog she met throughout her life loathed her with an unyielding passion despite her almost psychotic friendliness. Time and again, friends and family members would bring their dogs to our home, and after a few relentless days with Jamie, those dogs would trot briskly out of our house, glaring at their parents with a look that said, “Never again!”

Jamie fused herself to the side of my wife, who became her loyal protector and sovereign mistress, and eventually every relationship in her life became as predictable as the sunrise – she would be forever shunned and despised by her own species, and the bejeweled object of adoration for my patient, loving better half. She was loved or hated, never ignored.

The only complicated relationship she had in this world, in fact, was with me.

It’s no secret that there were days when we just couldn’t stand each other, and when those days came, she could turn sulking into high art. Can dogs pout? This dog pouted.

I am one of those frail, flustered souls whose top is forever threatening to blow, who stands ready to unleash a string of invectives at a moment’s notice, whether it’s because I’ve burned a piece of chicken in the kitchen, or because the officiating during a South Carolina football game is going off the rails, or because I’m stuck in traffic, or because I’m three minutes late for something unimportant, or because – yes – my dog is driving me crazy. There is always a Tornado Watch hovering around me.

Whenever my top did blow, Jamie wouldn’t stand for it. That old, kooky British aunt side of her would flare, and she would cast a steely side-eye in my direction, and you could see her thinking (presumably in a British accent), “Well. This is ridiculous. I’m just going to head to another room, or maybe even another floor of the house, if you’re going to be acting like that.”

And with a flourish, she’d turn and leave me. The dog who couldn’t leave anyone else alone could leave me behind without the slightest hesitation, and often did.

Team of Rivals

As the years passed, Jamie and I often resembled squabbling siblings, with my wife playing the role of beleaguered mom (who always seemed to side suspiciously with the one of us who had a fur coat). Sometimes I slept in the basement because she snored too loudly. For Jamie’s part, she made an elaborate show of turning away from me and decamping to my wife’s office the very second the lady of the house emerged downstairs to start her day.

And yet, like all great rivals, we were weirdly obsessed with each other, she and I.

Family members often told me that if I walked outside of the house for even a moment, she ran panic stricken to the windows, whining bitterly and pacing, as though she was shouting, “You’re not really leaving me, are you? You know I really do love you, right?”

And I got up with her every single dawn for 13 years, no matter how early she needed to get out there, to the point that when my wife and I went on vacation, I’d wake up at 5:30 every morning thinking I needed to be doing something for her, and feeling an empty pang when I realized she wasn’t there.

Top 10

- 1New

Top 25 College QBs

Ranking best '25 signal callers

- 2

Top 25 Defensive Lines

Ranking the best for 2025

- 3

Big Ten Football

Predicting 1st loss for each team

- 4Hot

College Football Playoff

Ranking Top 32 teams for 2025

- 5Trending

Tim Brando

Ranks Top 15 CFB teams for 2025

Get the Daily On3 Newsletter in your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

It seemed like we were always riding around in cars together, sent off into the world when we needed to be gotten rid of. Once we vacated the house for hours when my wife hosted a baby shower, aimlessly driving the streets of suburban Atlanta and listening to the radio. She and I would shuffle back and forth between family members’ homes during holidays back in South Carolina, or take off for a local park if the housecleaners were coming by (she maintained a lifelong suspicion of anyone wielding a vacuum cleaner). We were itinerant wanderers, the two of us, neither of us with many friends in this world, always seemingly in search of a place to call home, ships in search of a port of call, bouncing here and there with each other for company.

Her body had been in decline for months, that feverish puppy spirit finally sagging after thriving inside her well into old age, and then she started having trouble getting up out of seated position, and then the stairs started becoming a problem, and then my wife and I found ourselves saying things to each other like, “I’m just not sure how many more trips to South Carolina she’s got in her,” and then the vet (after yet another visit with yet another ailment) started talking to us in coded language about the end, and then a few weeks ago, the nosebleeds started.

I told myself I’d been preparing for this moment for 13 years.

We all know this is the way it is with dogs, that there’s a muffled sob pulsing beneath the entirety of our relationship with them, a dull ache underneath, because at all times and at every moment, it is all already sliding away.

I thought I was ready.

We were in one of those gray, frighteningly clinical rooms at the vet’s office, surrounded by the drab décor of the modern healthcare facility, and she was lying on the floor, wheezing loudly, almost as though she were snoring, her eyes as brown as the water in a salt marsh, her fur coat thick and dry. She was wearing the Gamecock collar, now tattered and itself a survivor of many years after my wife had threatened forever to replace it (always unsuccessfully).

I was lying beside her and I heard myself saying things that didn’t make any sense: You just close your eyes and you’re going to wake up on top of mountain and you’re going to be able to see far beyond the clouds. I thought I was ready, but I heard my body making moans I had never heard it make before. I took the collar with me when we left the vet’s office, and when we got home, I turned to my wife and brandished it and said, almost angrily, “I will keep this forever and we will never get rid of it” (as though anyone would ever try to take it away from me).

The next morning, I dropped my wife at the airport. She was leaving for California, a long- scheduled business trip coming at the worst possible time. We hugged each other for what seemed like a decade, both of us sniffling on the sidewalk in front of the terminal.

Driving away, I thought about the end and wondered why I had said that at the vet’s office – you close your eyes and you’re going to wake up on top of a mountain? Had she ever even been to the mountains?

Somewhere a memory stirred, a dusty one. I’m watching a country music documentary. She is lying beside me. Vince Gill is performing at the memorial service of his mentor and friend, George Jones. Gill starts to sing his song “Go Rest High on That Mountain,” but overcome by grief, he can’t continue. The crowd stands and helps him finish.

Before I know what I’m doing, I pull out my phone and pull up that song. I don’t listen to country much anymore – too many beefy dudes in cut-off flannel shirts, singing about beer and Friday night. But every now and then, when you really need it, it is the only music that can save you. It is the original music of mourning, the music of a broken heart, the music that many of our forefathers and foremothers brought with them from the hills of the old world to the hills of the new world, the music they sang to each other when their souls were sagging and needed repair, which was so very often.

The song started, that old wail from the mountains unfurling, and the vast Atlanta freeway stretched white in front of me under a blazing white sun, and as I felt thick tears stinging my cheeks, I knew it was cool where she was now on that mountaintop.

The Empty Collar on the Counter

They’ll put this on my epitaph: He was frustrated.

It’s a joke I’ve always told at my own expense, a way to poke fun at my brief outbursts when the tornado overtakes me, a way to make light of my old man foibles.

But now I see her water bowl sitting uselessly, and I see that empty Carolina collar on the counter, and I feel like I should be doing something for her and then there’s the empty ache of knowing she’s not there, and the joke doesn’t seem funny anymore, and I think of her face and the strangeness of our relationship and the years – all those years – we were together, and I think to myself, “Be nicer. For God’s sake, just be nicer.” Be the person your dog thinks you are, the old saying goes.

But that’s just the thing. My dog knew exactly who I was, and when I wasn’t acting right, she wouldn’t stand for it, and in her memory I have to be who I should have been for her and for everyone else all the time.

The question, at last, comes: Did my wife and I know she was just a dog?

We did. We knew she was just a dog.

We do not have children, and though I always prided myself on the fact that we’d avoided becoming the kinds of precious dog parents who pushed their puppy along in a stroller and dressed her in pajamas, we certainly did fret and fixate on her more than the average pet owner.

But we always knew she was just a dog.

Yes, she was just a dog who was with me at the worst moments of my life, just a dog who was still with me when I at last washed upon the shores of better days, weary and hopeful.

She was just a dog who made me laugh, just a dog who made me seethe, just a dog who left me speechless, just a dog who sat beside me on lonely nights when no other living creature did.

She was just a dog who loved me, just a dog who I loved, just a dog that I keep thinking will walk downstairs again one last time, casting a side-eye my way whenever I grumble too loudly.

I hope she knew how much I loved her, this dog, my sweet, strange, beautiful girl, my good-luck charm, just a dog who is forever part of me, just a dog that I will never forget.

Write me at [email protected].