South Carolina women's basketball: The Legend looks back

Alan Piercy is the author of A Gamecock Odyssey: University of South Carolina Sports in the Independent Era (1971-1991). The following was originally published on Alan’s South By Southeast newsletter.

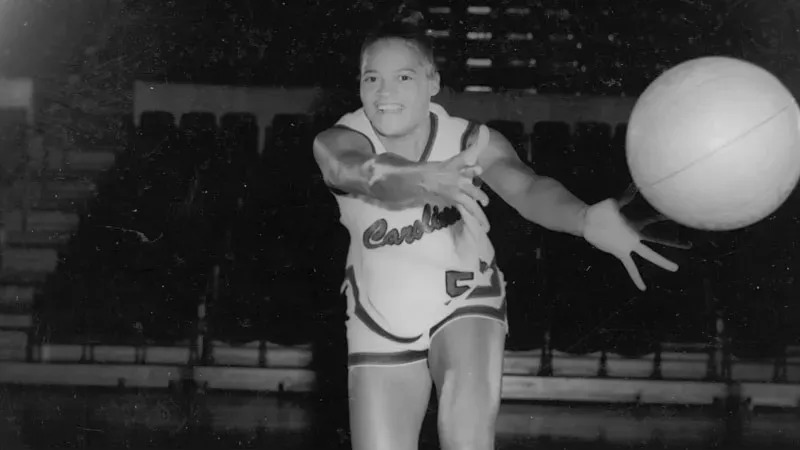

Decades removed from her playing days, the aroma of a gymnasium and the sound of sneakers on varnished wood still excite the former power forward who scorched nets and ground competition into submission beneath the hot lights of Frank McGuire Arena nearly 50 years ago.

Dawn Staley’s players refer to Sheila Foster simply as “The Legend.” Though a bout with breast cancer, devastating injuries from a late traffic accident, and the unrelenting passage of time have taken their toll, Foster’s spirit still emanates an enveloping energy, notable even through the ether of a cellular connection.

On Jan. 10, 2024, that spirit – that irrepressible energy – was nearly extinguished.

As Foster drove her burgundy 2005 Chevy Malibu to work along Highway 9 near her hometown of Boiling Springs in Spartanburg County, she approached a busy intersection across from North Grove Medical Center. She recalls seeing a car sitting in the opposite left-turn lane, the way you notice other cars in traffic – a fleeting recognition of its presence, but not much beyond. Possessing the right of way, Foster proceeded straight through the light at highway speed when the other car turned left in front of her unexpectedly. Her right foot pressed full on the brake pedal, Foster was unable to avoid the accident, hitting the car broadside in a violent collision.

“I just remember waking up and the only thing I said was ‘thank you Jesus’ three times. I never talked again for two days. I heard some ladies coming to me talking, but I couldn’t answer – I just stared. Everybody said I was in shock, and she said ‘Ma’am, are you ok?’ And I could hear, but I couldn’t talk, couldn’t turn my head. She said, ‘Let’s call the ambulance because your bones are hanging out of your foot.’ I woke up two days later with a cast around my leg. I didn’t know what happened until they told me later.”

Foster’s No. 53 jersey has hung in the rafters of Carolina Coliseum and Colonial Life Arena for some 43 years. From its lofty perch, that banner has overseen a program that has gone from budding national power to perennial Metro Conference champion to Southeastern Conference cellar dweller, and now to unprecedented heights, including three national championships under the leadership of Dawn Staley.

Foster became USC’s first multi-season All-America honoree, and left the Gamecock program as the career leader in points (2,266), rebounds (1,427), and double-doubles (72), then proceeded to hold those records over the course of four decades. Gamecock great A’ja Wilson surpassed Foster as the program’s points leader at the conclusion of her bronze-cast career in 2018. Aliyah Boston took the rebounding and double-double crowns in 2023 following an equally stellar four-year run. Foster now holds second place in all three categories.

Beyond her enduring prominence in USC’s record book, Foster remains foremost in the hearts of Gamecock fans all these years later. Columbia’s State newspaper recently conducted a poll to commemorate the “Mount Rushmore” of USC Women’s basketball. The State provided a list of 14 former stars spanning the 50-year history of the program, from which readers were tasked with voting for their top four.

Over 3,000 readers participated. Unsurprisingly, Wilson and Boston were shoe-ins for the honorific, both multi-year All-Americans and SEC Players of the Year who led national championship teams in 2017 and 2022, respectively. Two-time All-American and SEC Player of the Year Tiffany Mitchell also graced the top four.

Amidst those latter-day stalwarts, who garnered the highest vote total?

Sheila Foster.

Even amongst a cavalcade of Staley-era All-Americans, Foster’s star continues to shine. She is beloved by those who saw her play and revered by players and fans who have only heard the stories of her exploits.

“It means so much,” Foster says of the honor, “and it tells me that I got a lot of fans and friends that really love and care for me. When you got people like that, they don’t forget about you. I know there were great players that came after me and before me, and that’s not taking away from those players. It just means a lot.”

Foster has remained close to the program. Following the Gamecocks’ first national championship in 2017, she participated in the celebratory parade up Columbia’s Main Street – one of the only pre-Staley-era players in attendance. The following season, Staley invited her down for the championship ring ceremony, which initially confused her. “I didn’t know what I was there for,” Foster recalls, “and then she [Coach Staley] presented me with a ring, which just touched my heart.”

Of her long-held and now relinquished scoring, rebounding, and double-double records, Foster says simply, “Records are made to be broken.” She adds, “I cheered for them [Wilson and Boston], and when they broke it – all of them – I cheered for them.”

“I just appreciate all the respect Coach Staley gives me. All the players, they may not know me in person, but they know who I am. I’m there cheering for them all the time when I can get down there. It just means a lot to watch them. It brings tears to my eyes when I see them do some things, and it’s just a joy for me to be there to watch them play and to watch Coach Staley coach those girls. It brings back memories. It’s happy.”

The making of a legend

After years of club-level competition, Gamecock women’s basketball gained varsity status for the 1974-75 season in the aftermath of Title IX legislation signed into law by President Richard Nixon in June 1972. By December of that year, the University of South Carolina joined the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW), then the governing body for women’s college sports.

After three seasons under two different coaches who split time between basketball and other teaching duties on campus, the overall program record stood at 33-45. Athletics Director Jim Carlen wanted to upgrade the program and sought to hire a full-time coach and a proven winner.

Originally from Cookeville, Tennessee, Carlen first considered pursuing fellow Volunteer State native Pat Summitt of the University of Tennessee. Summitt had just finished her third season in Knoxville by leading her Volunteers to the AIAW Final Four. With Summitt comfortably ensconced in Knoxville, however, Carlen turned to another up-and-coming coach from Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia – an early powerhouse of the women’s collegiate game.

On Saturday, April 9, 1977, Carlen introduced Pam Parsons as the new women’s basketball coach and assistant athletics director for women’s sports.

Parsons quickly elevated the profile and identity of Gamecock women’s basketball. She introduced sleek new uniforms and quickly jettisoned the program’s “Carolina Chicks” nickname in favor of the less patronizing “Lady Gamecocks.”

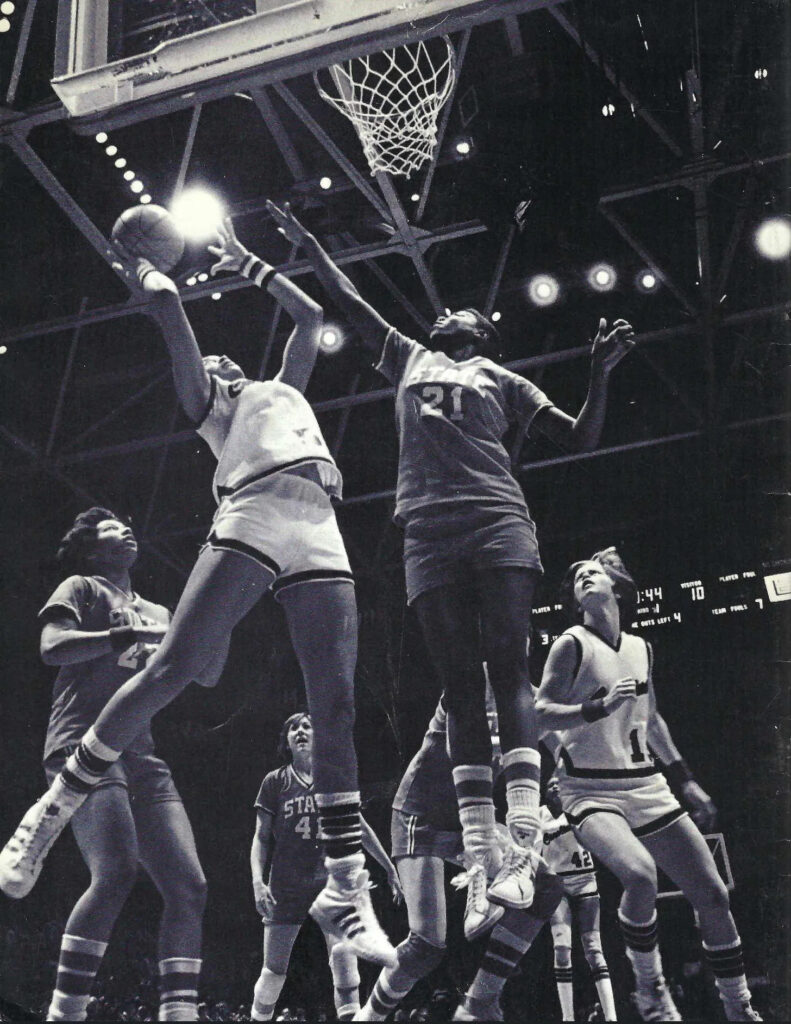

In prior seasons, the women’s team played its home games primarily at USC’s Booker T. Washington gymnasium, and even a few times at the Blatt P.E. Center on campus. The program had only appeared a smattering of times at Carolina Coliseum as a preliminary to men’s games. With Parsons at the helm, the Lady Gamecocks’ home games moved permanently to the Coliseum.

Parsons’ first team, 1977-78, featured upgraded talent, including Katrina Anderson, a junior transfer from Anderson Junior College (now Anderson University), who would break Denise Nanney’s nascent program scoring record during her two-year USC career. That team engineered a 14-game improvement over the prior season, finishing at 24-10, notching the program’s first 20-win season.

In her second season, 1978-79, Parsons welcomed her first blue-chip high school recruit in Foster. That team achieved the program’s first-ever national ranking following a shocking 73-49 home upset of No. 7-ranked Old Dominion, Parsons’ former team. The Gamecocks went on to capture that season’s Women’s National Invitational Tournament (WNIT), finishing with a 27-10 record. Foster, a season-long starter, ranked among the top 10 freshmen in the nation in both scoring and rebounding, averaging 14 points and nearly nine rebounds per game.

Parsons continued building her team, adding a 5-foot-10 freshman from Lansing, Michigan, Evelyn “Sweet E” Johnson, the kid sister to Earvin “Magic” Johnson, who shared her brother’s flair for assists and scoring. Local product Sharon Rivers and Becky Parker, a 5-foot-11 guard from Maryland who averaged 34.7 points per game as a high school senior, further solidified the roster.

The 1979-80 squad compiled a sterling 30-6 record, highlighted by the program’s first-ever win over powerhouse Tennessee, and reached the AIAW Final Four round in Mount Pleasant, Michigan. The Gamecocks faced their third matchup of the season with Tennessee in the semifinal, coming just short of qualifying for a national championship appearance in a 75-72 loss to the Lady Vols. Parsons’ team salvaged a third-place national finish in their final game, defeating Louisiana Tech, which featured a 5-foot-4 guard by the name of Kim Mulkey.

With 1,105 career points after just two seasons, Foster stood at third-best in program history, but she was just getting started.

By the end of her junior season, 1980-81, Foster had comfortably surpassed former teammate Katrina Anderson for the program’s all-time scoring title. While the team’s 21-9 finish was off pace by Parsons’ standards, the season marked a continuation of USC’s winning ways. However, in a precursor to problems that would unfold dramatically the following year, the Gamecocks were forced to forfeit eight games when the AIAW ruled that transfer forward Frani Washington was academically ineligible. The forfeit left the team with an official 13-17 finish.

1981-82, Foster’s senior season, was marked by the most bizarre and unfortunate series of events in program history. By this time, Parsons’ program was an established national power, brimming with talent, and ranked in the pre-season top 10. Seven games in, the team remained undefeated and had ascended to No. 2 in the polls – the program’s highest-ever ranking. It proved to be the high-water mark for Parsons and for the women’s program for many years to come, as growing whispers of improprieties dogged the coach, leading ultimately to her resignation on Jan. 4, 1982.

The remainder of the season was a wild ride of coaching changes, roster defections, a campus-wide tryout, a six-of-eight losing skid, plummeting poll standings, and ultimately, a stirring turnaround.

The team began to gel when it battled valiantly with only six players during a late January home game versus Tennessee. USC risked having to finish the game with fewer than five players on the court as three Gamecocks had four fouls late in the game. Though no one was ultimately disqualified, it was a testament to the ravages of roster defections following the early-season drama. Tennessee head coach Pat Summitt visited the Carolina locker room following the game to commend the Gamecocks’ courageous performance. USC’s interim head coach, Terry Kelly, told reporters, “An emotional burden is lifted. This team wants to play.”

USC reeled off 11 wins over its last 13 games, including a stirring one-point victory at No. 10 NC State in the final regular-season game. The 22-7 record was good enough to earn the program a bid to the first-ever NCAA women’s tournament. The Gamecocks defeated East Carolina, advancing to the Sweet Sixteen, before bowing out to future SEC rival, No. 14 Kentucky. Carolina had beaten the Wildcats at home just a few weeks prior before a scant 750 fans – difficult to imagine now, in an era when the Gamecocks have led the nation in attendance for 11-straight seasons, and averaged over 16,400 per home tilt in 2024-25.

The Gamecocks finished the season at No. 15 in the AP poll.

Foster scored 23 points and pulled down 19 rebounds in her final game, ending her career as the program leader in nearly every major statistical category.

Reflecting back on that time, Foster retains immense respect for Parsons in spite of the coach’s controversial exit. “I just have so much love for her, so much respect for her today. The only thing that really broke my heart was when they retired my jersey, they [USC officials] wouldn’t let her [Parsons] in the Coliseum,” Foster says of ceremonies to retire her No. 53 jersey before her final home game. It was a bittersweet ending to a legendary career as Foster’s No. 53 became the first women’s jersey retired in any sport at the University of South Carolina.

Years later, following South Carolina’s first NCAA Final Four appearance in 2015, Foster found herself annoyed by what media reports touted as the “first Final Four” in program history. It prompted her to reach out to her former coach.

Top 10

- 1Live

MBB Game Thread

South Carolina vs. Southern Miss

- 2

🏀 The Legend Looks Back

One of the great South Carolina WBB players

- 3Trending

OC "Warm" Board

Names that make sense

- 4

⚾ Sunday's Scrimmage

South Carolina fall baseball scrimmage notes and observations

- 5New

A&M Betting Odds

South Carolina opens as double-digit underdog

Get the Daily On3 Newsletter in your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

“They had a big article that said [the 2015 team] was the first to go to the Final Four, and it just ate me up inside, because I said no, I was on that [first] Final Four team. We went to the Final Four my sophomore year [1979-80]. I got [Coach Parsons’] number, and I finally got in touch with her. She said, ‘Sheila, that [1980 Final Four] was because of you.’ And I said, No, it’s because of us.”

Foster continued, “The final four IS the Final Four – doesn’t make a difference if it’s AIAW or NCAA or WXYZ.”

Her collegiate career concluded, Foster turned to professional basketball, which looked quite different for the women’s game in 1982 than it does today. The WNBA was a whisper of a dream, and lay a decade-and-a-half out into the future. The one US professional women’s league then in existence – the short-lived Women’s Professional Basketball League (WBL) was, at best, financially tenuous. It ultimately folded in the early ’80s after a four-season run.

Foster instead took her talents to Italy. “I played in Spinea three years, then went to Naples for a year, then played outside of Milan for two years.”

Asked if she picked up any Italian during that time, she said, “I sort of speak a little, but my contract did not say speak no language,” she says laughing, “they wanted me to put the ball in the basket.”

She did exactly that with characteristic grit and gusto across six seasons.

For even the very best, basketball doesn’t last forever. The rolled ankles take their toll. The accumulated soreness from old injuries, first nagging, then more insistent, begin to assert their dominion over once irrepressible energy and strength. Younger players, unencumbered by injury or doubt, come in waves at the start of every season, hungry to make their mark, eager to knock off the wily vet.

At some point, it ends, always more quickly than you thought it would.

After basketball, back to South Carolina

Foster returned home and started a family, resulting in a daughter, India (now 36), and a son, Stacy (now 32). She also went back to school, needing nine classes to earn her degree.

“I did four one semester and five the second semester, and walked,” she says, earning a BA in Interdisciplinary Studies with an emphasis in Physical Education.

She keeps a framed photo of her shaking the hand of former USC President James Holderman during the graduation ceremony in May 1990. Her trademark smile lit up the old Coliseum even as her No. 53 jersey looked on from the rafters above.

After graduation, she returned to Spartanburg County, where she taught and coached, ultimately ending up at her alma mater, Boiling Springs High School. There she returned to the sport that had narrated her life, spending years as an assistant, then as head coach of the junior varsity women’s team for 13 years. She became an institution – a living, breathing legend – beloved within the community for the impact she had on students and players, for the way she poured herself into the role, for her spirit of service, and for her abiding love of basketball and of Boiling Springs.

Along the way, she stayed close to the USC women’s program, following the ups and downs of the Nancy Wilson and Susan Walvius eras. In the Staley years, she has been a mainstay, regularly traveling to Saturday games.

“I’m just so proud that I chose the University of South Carolina. I wouldn’t change it for the world. My momma’s been gone sixteen years. Her and my uncle missed one game in four years. A lot of programs wanted me – I could have went anywhere. But choosing the University of South Carolina – I wouldn’t change it for the world. I’m still a Lady Gamecock. My blood still runneth garnet. And the way the program is growing, I’m just so happy. I’ll continue to cheer until I leave this world.”

“The doctors said amputate that foot”

When Foster woke up at North Grove hospital, just a stone’s throw away from the site of the accident two days prior, her life had changed. Surgeons installed 13 screws to stabilize the multiple compound fractures to her right foot and ankle. She also suffered four broken ribs and a cracked sternum.

“I got six screws and two plates in my chest for life,” she says.

She went to therapy four times a day. Mindset and muscle memory, long ago molded as an elite athlete, enabled her to push through the difficult recovery. “They [the doctors and therapists] know I don’t sit down and whine. I didn’t say I didn’t want to do it – whatever they told me to do, I did it.”

“My doctor said, ‘I’m gonna tell you every visit, Ms Foster, when you came to us, all the doctors said amputate that foot. You know what? You’re so blessed. We got your bones back in place, your screws haven’t shifted.’”

Reflecting on the help she had, Foster says, “I had some good people in there working with me. They were all so proud of me when I left. They all just clapped. There were so many hugs, and some of them I still keep in touch with.”

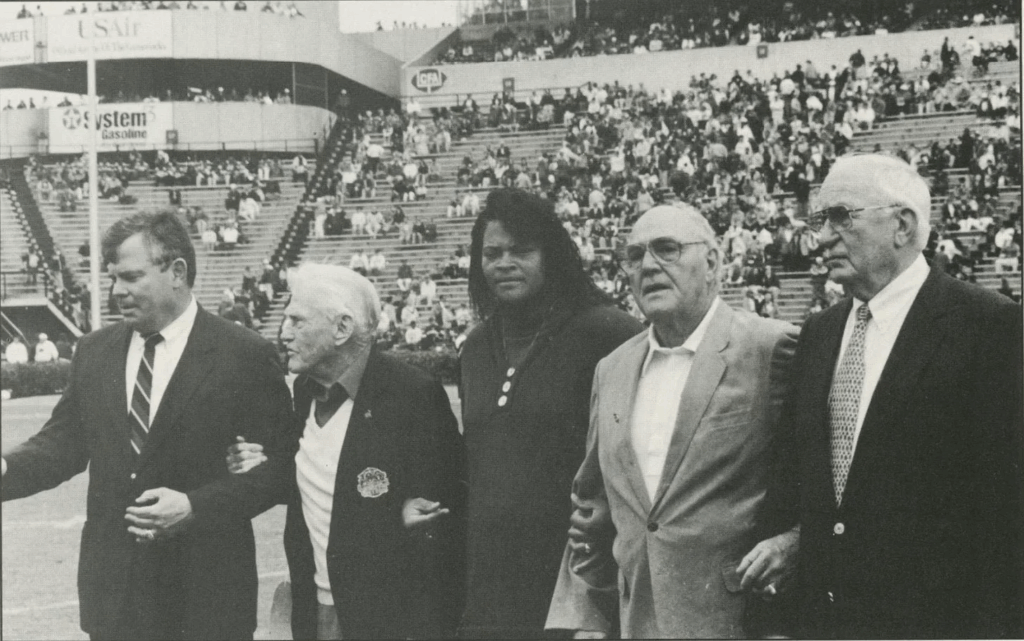

With the assistance of a walker, Foster was able to attend the annual South Carolina Athletic Hall of Fame ceremony last May, a scant four months after the accident. Her brilliant smile and genuine affection for everyone in the room belied the grueling recovery she was still very much going through. She still walks with a cane, but continues to put in the work and is improving day by day.

“I’m a fighter, and you can’t give up because something happened. When my number is called, I’ll be ready. I think He’s got me here for a reason.”

On a warm April Wednesday in 2022, the City of Columbia hosted a parade to celebrate the second national championship for the USC women’s basketball program. Thousands of fans, or “Fams,” as coach Dawn Staley proclaims them, lined both sides of Main Street for a victory parade to honor the team’s achievement. Among the VIP cars and parade floats, an assemblage of former players, mostly from the Staley era, joined in to celebrate what they had helped build.

As with the first championship celebration in 2017, Foster was in the thick of it.

From its lofty perch among the rafters of Colonial Life Arena, her long-retired No. 53 jersey has borne witness to the highs and the lows, the challenges and the triumphs of the Gamecock program over the course of four decades since Foster herself roamed the old Tartan floor of Frank McGuire Arena, generally having her way with opponents while collecting records by the bushel.

Foster has been in remission since a scare with breast cancer in 2014 and has battled back from two knee replacements. She was hospitalized briefly in 2020 with double pneumonia and retired after 13 seasons from coaching to focus on her health. All that before the 2024 accident.

Like the South Carolina women’s basketball program of which she remains such an integral part, Foster has seen the greatest of highs and the darkest of lows.

But on that warm April Wednesday in Columbia, as the championship parade made its way south along Main, Foster smiled her 1,000-watt smile, absorbing the love of thousands of well-wishers, many of whom had never seen her ply her trade under the Coliseum lights those many years ago.

In that moment, a radiant spring sun reflecting on her face, the universe came full circle in a beautiful and healing way. Foster says of the experience, “It was the greatest feeling in the world.”