Tennessee, Oklahoma and the 1939 'Orange Brawl'

The car pulled in front of the Tennessee football offices long before daylight.

In the middle of winter, a little more than a month after the Vols ended an up-and-down 1937 campaign with a win over Ole Miss, Robert Neyland stepped out and unlocked the door as his assistant coaches filed in behind him.

Neyland had lost just 12 games in 12 seasons as Tennessee’s head coach, but five of those losses had come in the previous two years.

On a frigid January morning in 1938, he was determined not to repeat it.

Most mornings for the next three months, Neyland and his staff arrived early. Players soon followed at 6 a.m. for spring drills at Shields-Watkins Field. Five players ended up with broken bones while the rest of the team limped into April.

But by the end of it, Neyland had built one of his greatest teams—one that went unscored upon in eight games, allowed just 16 points in three others, became the darling of several national champion selectors and began one of the greatest dynasties in college football history.

It all accumulated in an Orange Bowl bout with Oklahoma that featured fractured jaws, bloody noses and a 17-0 Tennessee triumph on a sun-soaked afternoon in Miami on Jan. 2, 1939—More than 87 years before No. 14 Tennessee (6-2, 3-2 SEC) will meet the No. 18 Sooners (6-2, 2-2) at Neyland Stadium for the sixth time on Saturday (7:30 p.m. ET, ABC).

“Those hard running, vicious-blocking, savage-tackling men of Major Bob Neyland left behind plenty for the more than 30,000 fans to remember them by as they crushed the Sampsonian Oklahoma Sooners,” Knoxville News-Sentinel’s Bob Wilson wrote. “They’ve undoubtedly reached the greatest heights in Tennessee football history.”

The ‘greatest team the old Volunteer State has ever produced’

Ed Moliniski shouted to Robert Neyland as he walked into Alumni Memorial Gymnasium one afternoon in 1938.

Moliniski, who split his time between playing guard for the Tennessee football team and boxing, was sparring in the gym when he challenged Neyland to a few rounds.

“‘I don’t want to hurt you, Moliniski,’” he recalled Neyland saying in “Neyland: The Gridiron General,” by Bob Gilbert.

Neyland had been a standout boxer at West Point, where he played football and baseball nearly 25 years earlier. But the 20-year-old Moliniski was confident he could take him. Neyland stepped into the ring and the two sized each other up for a moment.

Moliniski threw a couple of punches, then was suddenly laying on his back.

“‘I just wanted to show you what a left jab followed by a real left hook could do,’” Moliniski remembered Neyland saying as he stood over him.

Moliniski was one of a handful of returning players that Tennessee was going to rely on in 1938. The group included captain and end Bowden Wyatt, guard Bob Sufferidge and a star-studded backfield trio of George Cafego, Babe Wood and Bob Foxx.

They came from different regions of the country, but all shared similar backgrounds.

Moliniski was a three-sport star at Massillon High School in Ohio. Cafego was discovered in West Virginia, where he starred in football and baseball. Wyatt was from just down the road in Kingston.

All three players told Neyland that they couldn’t afford college, but that it was their best chance to get out of poverty. All three went on to become All-Americans at Tennessee.

Moliniski retired as a Doctor in Memphis. Wyatt became Tennessee’s head coach in 1955 and Cafego served as an assistant on his staff—and for three other Vols head coaches. Both were inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame.

On the eve of the 1938 season, it was unclear what their on-field contributions would lead to, though.

One preseason publication noted that the Vols were “not-so-prominent” heading into the season after falling short of lofty expectations in 1937. But that didn’t stop the optimism in Knoxville.

Knoxville Journal columnist Tom Anderson wrote that summer that, “there is a persistent hunch, intuition, presentment, or whatever you want to call it, that Bob Neyland’s outfit is headed for the upper regions.”

At the newly-expanded Shields-Watkins Field and in front of a record crowd of 20,000, the Vols rolled to a 26-3 win over Sewanee in their opener. Wyatt and Foxx each scored, but Neyland wasn’t impressed.

“The team looked ragged,” Neyland told reporters after the game. “It is going to take an awful lot of work to get in shape for the schedule coming now.”

Neyland started his second team the following week against Clemson. Tennessee fell behind early and Neyland put the first teamers in, leading to a 20-7 victory.

Only one other team scored on the Vols’ vaunted defense the rest of the season as Tennessee piled up win after win over Auburn, Alabama, The Citadel, LSU, Chattanooga, Vanderbilt, Kentucky and Ole Miss.

The 13-0 blanking of the Crimson Tide at Legion Field in Birmingham was arguably the most satisfying.

Tennessee hadn’t beaten Alabama in six years, and the Crimson Tide were riding a 21-game regular season win streak and coming off of a Rose Bowl appearance. No one gave the Vols much of a chance, but Cafego ran 19 times for 145 yards and the Vols pitched their second-straight shutout.

“Without Cafego today, Tennessee was a better ball team than we were,” Alabama line coach Hank Crisp said. “With Cafego—well, they were a hell of a lot better.”

Top 10

- 1Breaking

Matt Rhule

Signs extension, massive buyout

- 2Trending

Louisiana Governor

Fires shot at LSU AD

- 3

Oklahoma-Tennessee

Playoff elimination game

- 4Hot

Nick Saban

Roster spend determines best job

- 5

Arch Manning

Texas updates status vs. Vandy

Get the Daily On3 Newsletter in your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

Tennessee went from unranked to No. 8 in the polls the following week. The Vols jumped to No. 4 four weeks later and won their first SEC title with a 47-0 drubbing of Ole Miss in Memphis, moving them to No. 2 and setting them on a course for the Orange Bowl against unbeaten and No. 4 Oklahoma.

TCU, led by quarterback Davey O’Brien, finished No. 1 in the post-regular season polls, but Dunkel, Litkenhous and a bevy of other polling services tabbed 10-0 Tennessee, which outscored opponents an astounding 276-16, as the national champion.

“Many rate the Vols the greatest machine to trod on a Dixie football field,” Raymond Johnson of the Nashville Tennessean wrote on Dec. 5, 1938. “They say it is more brilliant than John Heisman’s Georgia Tech team of 1917 or Wallace Wade’s Alabama crew of 1930…It certainly is the greatest team the old Volunteer State has ever produced.”

The ‘Orange Brawl’

Robert Neyland called for Joe Little.

The Tennessee head coach watched center Jim Rike get into another tussle with Oklahoma defenders well after a play and had enough. He wanted Little to replace him.

One play later, Little was lifted off of the turf after catching an upper cut to the chin as he was snapping the ball on a punt. He regained his footing and ran down the field after his offender before landing a blow of his own.

Little stood over him, barking at him to get up before officials stepped in and tossed him out of the game. He joined Ed Molinksi, who was ejected for returning a punch earlier in the game, on the bench.

“It was the Orange Bowl, but a more fitting name would have been the ‘Orange Brawl,’ Knoxville Journal sports editor Russ Bebb later wrote in his book “The Big Orange.”

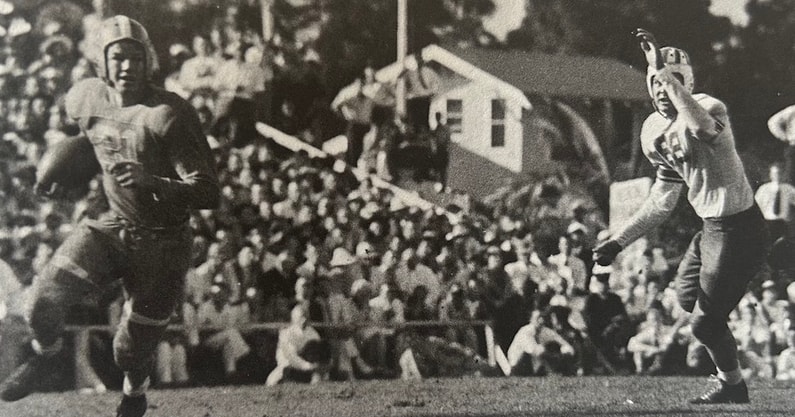

A clear blue sky, palm trees and 30,000 mostly-orange-clad spectators provided an odd backdrop for the grand finale between the Vols and Sooners that turned into a boxing match.

Cafego set the tone when he went head-to-head with Oklahoma All-American end Waddy Young, sending him spinning through the air after a block on the first play of the game.

“It was devastating,” Fred Russell reported for the Nashville Banner. “Heads bumped, bodies crashed together and teeth rattled. Never have two teams hit as hard.”

The tension between the two teams had been building for a week. Neyland denied Oklahoma beat writers the opportunity to watch Tennessee practice, something they grumbled about in their newspapers.

Neither team was allowed to practice at Burdine Stadium, but Neyland was tipped off that Sooners’ head coach Tom Stidham had made some kind of backdoor arrangement with the City of Miami to practice there.

It all boiled over into the first play when Cafego went surging into Waddy.

“When Waddy Young fell with his great limbs sprawled, Oklahoma fell with him,” Memphis Commercial Appeal sports editor Walter Stewart wrote.

It summed up the afternoon. It might have been a knock-down, dragout, slugfest but it was one that Tennessee was in control of, even with 130 yards of penalties levied against it.

Bob Foxx scored on a reverse to give the Vols the lead for good. Bowden Wyatt’s extra point attempt was blocked, but he snagged the ball out of the air and scored. Babe Wood landed the knockout blow on a 15-yard touchdown run in the fourth quarter and Tennessee finished off its first unbeaten, untied season in 14 years with a 17-0 win.

Sports writers clamored for a game between the Vols and TCU to determine the national champion. Tennessee’s dominance of Oklahoma had assured many that it was the best team in the country.

“Oklahoma never had a chance,” the Oklahoma News’ Jim Hopkins opined. “I am also convinced that Major Bob Neyland’s Volunteers could beat TCU and Southern Cal, and is the best football team of the 1938 season.”