You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Those statistics, however, cannot address the fundamental question: When a shooting might be justified by department standards, are police more likely actually to shoot if the civilian is black? Only our data can answer this question, because it contains information on situations in which a shooting might meet departmental standards but didn’t happen. The answer appears to be no.

No matter how we analyzed the data, we found no racial differences in shootings overall, in any city in particular, or in any subset of the data. I have grappled with these results for years as I witnessed videos of unmistakable police brutality against black men. How can the data tell a story so different from what we see with our eyes?

Our analysis tells us what happens on average. It isn’t average when a police officer casually kneels on someone’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. Are there racial differences in the most extreme forms of police violence? The Southern boy in me says yes; the economist says we don’t know.

Mr. Fryer is a professor of economics at Harvard

No matter how we analyzed the data, we found no racial differences in shootings overall, in any city in particular, or in any subset of the data. I have grappled with these results for years as I witnessed videos of unmistakable police brutality against black men. How can the data tell a story so different from what we see with our eyes?

Our analysis tells us what happens on average. It isn’t average when a police officer casually kneels on someone’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. Are there racial differences in the most extreme forms of police violence? The Southern boy in me says yes; the economist says we don’t know.

Mr. Fryer is a professor of economics at Harvard

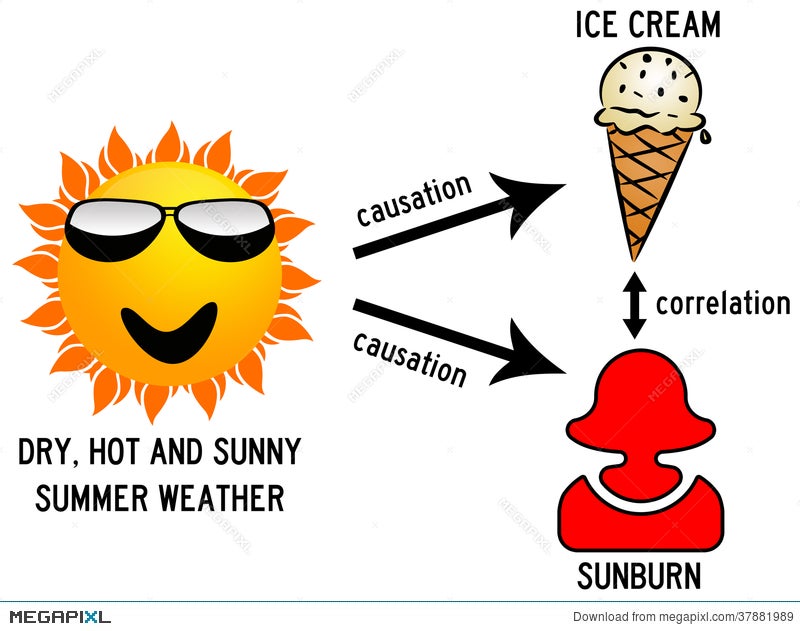

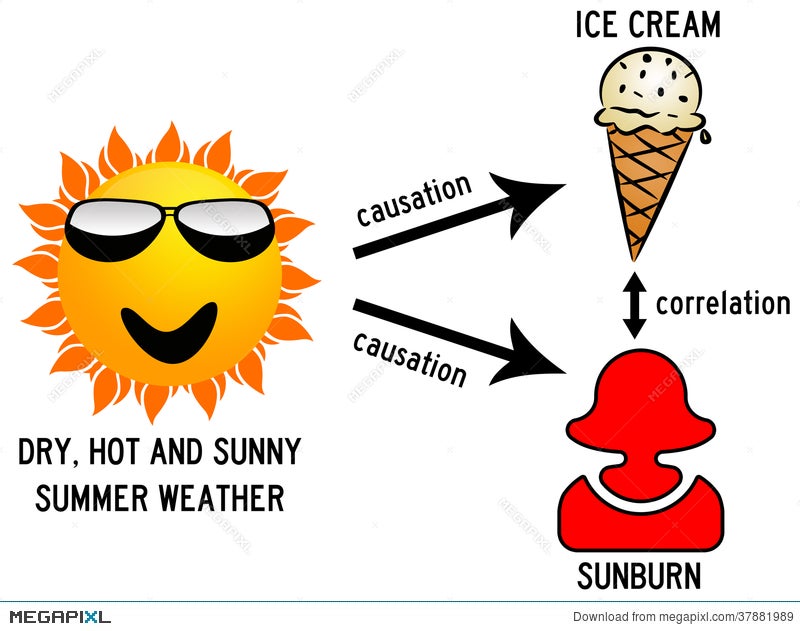

Other scholars criticized Fryer's study, arguing that due to selection bias, he was unable to draw any conclusions about racial bias in shootings from police stops. If police are more likely to stop a black person than a white person, then the average white person that they stop might be dissimilar to the average black person (for example, the white person might be behaving in a more threatening manner), thus leading to faulty inferences about racial bias in shootings. A 2020 study by Princeton University political scientists disputed the findings by Fryer, saying that if police had a higher threshold for stopping whites, this might mean that the whites, Hispanics and blacks in Fryer's data are not similar. Nobel-laureate James Heckman and Steven Durlauf, both University of Chicago economists, published a response to the Fryer study, writing that the paper "does not establish credible evidence on the presence or absence of discrimination against African Americans in police shootings" due to issues with selection bias

upon launching an investigation into Title IX complaints against him alleging sexual harassment. Fryer alleged that he was "unfairly scrutinized ... for his skin color." Harvard confirmed that its Office for Dispute Resolution received complaints against Fryer in January, March, and April 2018.

In July 2019, Fryer was suspended from the Harvard faculty for two years without pay, a disciplinary action determined by a panel of tenured faculty. Harvard also determined that, after returning from suspension, Fryer cannot be an adviser or supervisor, have access to graduate fellows, or teach graduate workshops, but can teach graduate classes. Fryer had been one of Harvard's most highly paid professors. As the sanctions took effect, Harvard permanently closed EdLabs in September 2019.

The 'scientific method' which characterises' hard sciences is simply impossible in economics, theoretically and practically. Physics, the most directly comparable hard science, is characterised by 'truth' and by hard rules. Economics by its nature studies humans and ultimately human nature is determined by things far beyond our understanding and ability to model mathematically or analytically. We can make a 'best guess' and get close but there is no comprehensive truth in economics. Everything is a heuristic or a rule of thumb rather than an absolute truth.

Practically, its difficult to apply the scientific method of experimentation to economics. Generally, where a physicist can conduct a controlled experiment or a chemist can mix two elements, if I want to test how unemployment affects wages I can't (ethically) run an experiment. What I can do is look at data and try and manipulate it in a way that gives the correct result (and by correct I mean the true result, not necessarily the one I want!) Attempts to run experiments in economics are possible, important but ultimately limited. We sometimes have people play lab games to test the validity of economic theory but we have to be careful that we understand why players are doing what they are. We only observe actions in economics. Not motivations. Particles don't have motivations, but humans do, and what they are will affect how they act under different rules.

On a slightly more technical level, the 'economic method' is fundamentally different, although this is a highly esoteric point. I'm making it because some people try to associate economics with physics because of the overwhelming use of mathematics. This is wrong, because their use is fundamentally different.

Hard sciences use mathematics and statistics to measure and explain natural phenomena. Economists use it to analyse. Its called 'axiomatic mathematics' and what it means is that I start with a set of assumptions (people maximise their happiness, people have a fixed income, there are N goods they can choose from etc) and then I figure out the logical conclusion of those assumptions. That is something economics does all the time which is pretty exclusive and it is because it is seeking to explain something which is practically unexplainable, and so we have to strictly define the circumstances under which our theory will hold.

Apologies if this was too long or technical, I'm happy to clarify (or debate) any of it. The tl;dr is that economics is not a hard science because it is explaining something so fundamentally different which requires the methods used to be fundamentally different is superficially similar.

Practically, its difficult to apply the scientific method of experimentation to economics. Generally, where a physicist can conduct a controlled experiment or a chemist can mix two elements, if I want to test how unemployment affects wages I can't (ethically) run an experiment. What I can do is look at data and try and manipulate it in a way that gives the correct result (and by correct I mean the true result, not necessarily the one I want!) Attempts to run experiments in economics are possible, important but ultimately limited. We sometimes have people play lab games to test the validity of economic theory but we have to be careful that we understand why players are doing what they are. We only observe actions in economics. Not motivations. Particles don't have motivations, but humans do, and what they are will affect how they act under different rules.

On a slightly more technical level, the 'economic method' is fundamentally different, although this is a highly esoteric point. I'm making it because some people try to associate economics with physics because of the overwhelming use of mathematics. This is wrong, because their use is fundamentally different.

Hard sciences use mathematics and statistics to measure and explain natural phenomena. Economists use it to analyse. Its called 'axiomatic mathematics' and what it means is that I start with a set of assumptions (people maximise their happiness, people have a fixed income, there are N goods they can choose from etc) and then I figure out the logical conclusion of those assumptions. That is something economics does all the time which is pretty exclusive and it is because it is seeking to explain something which is practically unexplainable, and so we have to strictly define the circumstances under which our theory will hold.

Apologies if this was too long or technical, I'm happy to clarify (or debate) any of it. The tl;dr is that economics is not a hard science because it is explaining something so fundamentally different which requires the methods used to be fundamentally different is superficially similar.

2020 update: The specific flaws of Roland Fryer's paper have now been characterized in two studies (by other scholars, not myself). Knox, Lowe, and Mummolo (2019) reanalyze Fryer's data to find it understates racial biases. Ross, Winterhalder, and McElreath (2018) do something similar through a statistical simulation.

Fryer’s analysis is highly flawed, however. It suffers from major theoretical and methodological errors, and he has communicated the results to news media in a way that is misleading. While there have long been problems with the quality of police shootings data, there is still plenty of evidence to support a pattern of systematic, racially discriminatory use of force against black people in the United States.

Breaking down the analysis of police shootings in Houston

There should be no argument that black and Latino people in Houston are much more likely to be shot by police compared to whites. I looked at the same Houston police shooting dataset as Fryer for the years 2005-2015, which I supplemented with census data, and found that black people were over 5 times as likely to be shot relative to whites. Latinos were roughly twice as likely to be shot versus whites.

Fryer’s analysis is highly flawed, however. It suffers from major theoretical and methodological errors, and he has communicated the results to news media in a way that is misleading. While there have long been problems with the quality of police shootings data, there is still plenty of evidence to support a pattern of systematic, racially discriminatory use of force against black people in the United States.

Breaking down the analysis of police shootings in Houston

There should be no argument that black and Latino people in Houston are much more likely to be shot by police compared to whites. I looked at the same Houston police shooting dataset as Fryer for the years 2005-2015, which I supplemented with census data, and found that black people were over 5 times as likely to be shot relative to whites. Latinos were roughly twice as likely to be shot versus whites.

Those statistics, however, cannot address the fundamental question: When a shooting might be justified by department standards, are police more likely actually to shoot if the civilian is black? Only our data can answer this question, because it contains information on situations in which a shooting might meet departmental standards but didn’t happen. The answer appears to be no.

This is a limitation on the data, but it's not the main criticism of Fryer.

The principle issue is that Fryer controls for the rate of interactions with the police, but that rate is effectively determined entirely by police officers (who have wide discretion in who to stop/pull over) and departmental policy (i.e. how many patrols get assigned to which neighborhoods). This means that we've already prevented ourselves from considering one major avenue where we have very solid evidence that racial bias is introduced, and, in particular, it means that the group "white people stopped by the police" is not identical to the group "black people stopped by the police:" black folks are substantially less likely to be engaged in criminal activity when they interact with the police. This article covers some of the methodological issues pretty well; if you're pressed for time you can scroll down to the infographic, which helps visualize some of the difficulty in this kind of analysis.

But the short version is this -- if the police are stopping more 'innocent' black folks (i.e. people with no contraband, weapons, or outstanding warrants on them at the time), but they're still being killed at a roughly equal rate to whites, this doesn't demonstrate an absence of bias at all. Quite to the contrary, it suggests that there is racial bias at play: there appears to be a lower threshold for killing black suspects than white ones.

As an analogy, imagine you're testing a new medication to prevent breast cancer, and you let doctors just recruit people for the study that they think could benefit from it. The doctors recommend that most of their female patients join their study, because breast cancer is a common problem for women, but they only recruit a handful of men who show some additional risk factor (e.g. a particular genetic marker). At the end of the study, you find that 0.1% of people who take the medication develop breast cancer within one year. Upon further examination of the data, you realize that this number is true across all groups: i.e. 0.1% of men who take the medication develop breast cancer, and 0.1% of women who take the medication develop breast cancer. Would you say that this medication is equally dangerous for all groups? If so, you're missing the fact that these two groups didn't have equal risks for breast cancer to begin with -- the drug could actually be lowering the risk for one group, while raising it for the other.

The principle issue is that Fryer controls for the rate of interactions with the police, but that rate is effectively determined entirely by police officers (who have wide discretion in who to stop/pull over) and departmental policy (i.e. how many patrols get assigned to which neighborhoods). This means that we've already prevented ourselves from considering one major avenue where we have very solid evidence that racial bias is introduced, and, in particular, it means that the group "white people stopped by the police" is not identical to the group "black people stopped by the police:" black folks are substantially less likely to be engaged in criminal activity when they interact with the police. This article covers some of the methodological issues pretty well; if you're pressed for time you can scroll down to the infographic, which helps visualize some of the difficulty in this kind of analysis.

But the short version is this -- if the police are stopping more 'innocent' black folks (i.e. people with no contraband, weapons, or outstanding warrants on them at the time), but they're still being killed at a roughly equal rate to whites, this doesn't demonstrate an absence of bias at all. Quite to the contrary, it suggests that there is racial bias at play: there appears to be a lower threshold for killing black suspects than white ones.

As an analogy, imagine you're testing a new medication to prevent breast cancer, and you let doctors just recruit people for the study that they think could benefit from it. The doctors recommend that most of their female patients join their study, because breast cancer is a common problem for women, but they only recruit a handful of men who show some additional risk factor (e.g. a particular genetic marker). At the end of the study, you find that 0.1% of people who take the medication develop breast cancer within one year. Upon further examination of the data, you realize that this number is true across all groups: i.e. 0.1% of men who take the medication develop breast cancer, and 0.1% of women who take the medication develop breast cancer. Would you say that this medication is equally dangerous for all groups? If so, you're missing the fact that these two groups didn't have equal risks for breast cancer to begin with -- the drug could actually be lowering the risk for one group, while raising it for the other.

Finally, analysis of police shooting data as a function of county-level predictors suggests that racial bias in police shootings is most likely to emerge in police departments in larger metropolitan counties with low median incomes and a sizable portion of black residents, especially when there is high financial inequality in that county.

To my dismay, this work has been widely misrepresented and misused by people on both sides of the ideological aisle.

Several scholars have rightly pointed out that these data all begin with an interaction, and suggested that racist policing manifests itself in more interactions between blacks and the police. The impact of this hypothesis in our shootings data seems minimal. The results on police shootings are statistically the same across all call types—ranging from officer-initiated contact with a suspicious person (where racism in whom to police is likely paramount) to a 911 call of a homicide in progress (where interaction with the potential suspect is more likely independent of race).

Are the data nationally representative? We don’t know. But at least two other studies, both published in 2016—by Phillip Atiba Goff et al. and Ted R. Miller et al.—have since found the same using different data.

Several scholars have rightly pointed out that these data all begin with an interaction, and suggested that racist policing manifests itself in more interactions between blacks and the police. The impact of this hypothesis in our shootings data seems minimal. The results on police shootings are statistically the same across all call types—ranging from officer-initiated contact with a suspicious person (where racism in whom to police is likely paramount) to a 911 call of a homicide in progress (where interaction with the potential suspect is more likely independent of race).

Are the data nationally representative? We don’t know. But at least two other studies, both published in 2016—by Phillip Atiba Goff et al. and Ted R. Miller et al.—have since found the same using different data.

The principle issue is that Fryer controls for the rate of interactions with the police, but that rate is effectively determined entirely by police officers (who have wide discretion in who to stop/pull over) and departmental policy (i.e. how many patrols get assigned to which neighborhoods). This means that we've already prevented ourselves from considering one major avenue where we have very solid evidence that racial bias is introduced, and, in particular, it means that the group "white people stopped by the police" is not identical to the group "black people stopped by the police:" black folks are substantially less likely to be engaged in criminal activity when they interact with the police. This article covers some of the methodological issues pretty well; if you're pressed for time you can scroll down to the infographic, which helps visualize some of the difficulty in this kind of analysis.

Fryer’s analysis is highly flawed, however. It suffers from major theoretical and methodological errors, and he has communicated the results to news media in a way that is misleading. While there have long been problems with the quality of police shootings data, there is still plenty of evidence to support a pattern of systematic, racially discriminatory use of force against black people in the United States.

If black America were getting "woke" to DT, they wouldn't be supporting Biden at 92%.

I always love the ad hominem attacks. It always lets me know when I have accomplished my goals.

Everybody understands your primary goal is to piss people off with your pedantry and other forms of willful and otherwise ignorance/immaturity, which I’m ofcourse immune to because I know you and what you’re doing.

But that doesn’t matter. Your only real insult is to the truth, which contributes to lives lost and destruction, for political ends.

You only lose when you achieve all your goals(you wont),and those seduced by your poorly reasoned arguments are equally as lost. To those who aren’t yet, just look at the type of people who purvey these lies and think harder about what’s being claimed and what’s actually happening; this is not the extension of the civil rights movement, but it’s racist, hate-fueled antithesis.

Take the partisan blinders off. You’re on the wrong side of history, only question remains to be answered is how wrong.

But that doesn’t matter. Your only real insult is to the truth, which contributes to lives lost and destruction, for political ends.

You only lose when you achieve all your goals(you wont),and those seduced by your poorly reasoned arguments are equally as lost. To those who aren’t yet, just look at the type of people who purvey these lies and think harder about what’s being claimed and what’s actually happening; this is not the extension of the civil rights movement, but it’s racist, hate-fueled antithesis.

Take the partisan blinders off. You’re on the wrong side of history, only question remains to be answered is how wrong.

My only real goal is to provide people with factual data/evidence that a certain group of this board wants to control with disinformation and fear-mongering tactics. Your method of if you can control the information they absorb, you can control their feelings and beliefs. It's the only way a certain faction can maintain power. It's been the utilized method for generations.Everybody understands your primary goal is to piss people off with your pedantry and other forms of willful and otherwise ignorance/immaturity, which I’m ofcourse immune to because I know you and what you’re doing.

But that doesn’t matter. Your only real insult is to the truth, which contributes to lives lost and destruction, for political ends.

You only lose when you achieve all your goals(you wont),and those seduced by your poorly reasoned arguments are equally as lost. To those who aren’t yet, just look at the type of people who purvey these lies and think harder about what’s being claimed and what’s actually happening; this is not the extension of the civil rights movement, but it’s racist, hate-fueled antithesis.

Take the partisan blinders off. You’re on the wrong side of history, only question remains to be answered is how wrong.

Your goal is to convince people you know for more than you do, and that only you and select others can appropriately dissect and discern the information for them and relay it to them in the correct manner. You try to utilize terms you clearly Google and have no in-depth knowledge of. It is nothing more than charlatan tactics utilized by those that are inadequate at truly accepting the realities.

You utilize sources that clearly only agree with your point of view and refuse to even consider that which might cast doubt on your forced beliefs. Then it is routinely pointed out that your data and sources meets the same merits as those you were previously disregarding as inadequate or insufficient. You value them more if they are a member of the ethnicity group with whom the debate is over. Initially oblivious to the countless sources who contest their beliefs and research and provide ample evidence for why it is flawed. You fail to consider the personal backgrounds and actions of these supported figures. When that is all presented, you drift through social media to find the next figure that agrees with you. It's a classic representation of someone not able to articulate the points for themselves and argue them based off of the understandings.

This all just points to someone with a classic personality complex. Getting to witness that manifestation occur through our conversing isn't not entertaining to me. I will admit that much.

You’re lying to people, deceiving them in this instance like all others.

But it’s easiest to see in the fine people hoax because it does’t require thinking.

This is all well beyond the pale of typical political spin... it’s flat out lying, creating the very problem your racist “anti racist”rhetoric claims it wants to solve.

But it’s easiest to see in the fine people hoax because it does’t require thinking.

This is all well beyond the pale of typical political spin... it’s flat out lying, creating the very problem your racist “anti racist”rhetoric claims it wants to solve.