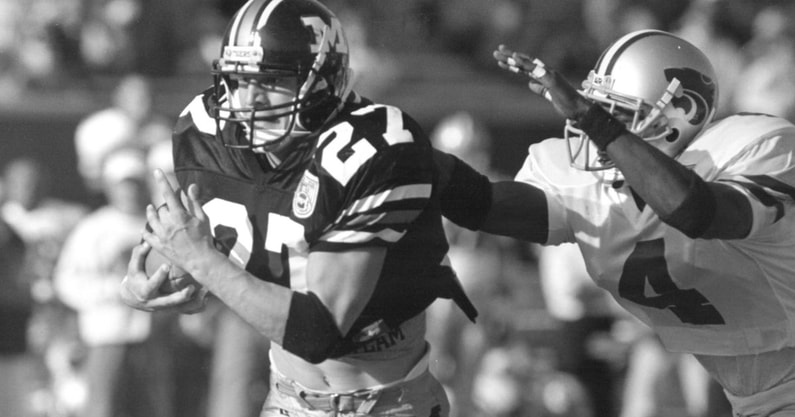

Brock Olivo: Mizzou legend, coach who found life beyond football

When former Mizzou running back Brock Olivo suffered a foot injury in 2002, he could have worked his way back and continued his NFL career. He had spent four seasons with the Detroit Lions to that point.

But instead, Olivo decided he wanted to expand his life. He didn’t want to just be a football player. He wanted to become a well-rounded person.

“I decided to walk away because I just wasn’t the player I was at one time,” Olivo said. “I had some ability left, but I certainly didn’t intend to continue my career anywhere.”

So Olivo retired from the NFL and went in search of whatever was next. He returned to Columbia, Mo., and had lunch with one of his former professors. Claudio Da Soller, who helped teach Olivo Italian in school, asked what Olivo wanted to do next.

“I’ll never forget, we were having coffee and he said, ‘So, what are you going to do now Brock?’” Olivo said. “I said, you know Claudio, I’m trying to figure that out right now. What I was thinking about doing was kind of taking a sabbatical, going to Italy and trying to look up my ancestors on my father’s side.”

Olivo said he wanted to spend as much time as he could in Italy finding his roots, but a travel visa only lasted three months. So his professor suggested a possible work Visa that would last a bit longer.

“He said, ‘You know, American football exists in Italy,’” Olivo said. “… Sure enough, I went kind of fishing on the internet and I looked it up and the teams actually had websites.”

Though playing oversees is moderately common in professional baseball, and a regular option in professional basketball, it’s not a common path for football players.

Olivo got to work sending emails to see if any of the teams in the Italian Football League and it didn’t take long to get some interest. In fact, having a recently retired NFL player join the coaching staff was intriguing for basically every team. Though he had no intention of joining the active roster to play. But that changed quickly.

“I wrote emails to each of the franchises over there,” Olivo said. “Within 24 hours, I had an inbox full of responses. And they were ecstatic at the idea of a fresh out of the NFL guy coming over and just lending a hand. … And of course, before I got there, they talked me into playing.”

Interest in Italy

Olivo’s Italian heritage intrigued him throughout his life. Growing up in Hermann, Mo., Olivo would make regular trips to Pennsylvania to visit with grandparents.

“We would go back to where my father grew up, in western Pennsylvania, right outside of Pittsburgh,” Olivo said. “A little coal mining town that was all Italian. … It was like being transported into another world.”

Olivo said his grandparents would speak a combination of English and Italian, his great grandmother spoke mostly Italian in the house. Luciano Pavarotti was the consistent music coming through the record player.

“My grandma was belting out Pavarotti in the kitchen and crying because she was moved by it,” Olivo said.

The food was all Italian. A change from what Olivo primarily ate in a mostly German town in Missouri.

And he said his grandfather imparted a message to Olivo at a young age. The family history mattered, where the Olivo’s came from mattered and the young Olivo should take an interest.

“He showed me Italy on the world map, and he explained to me where our family came from,” Olivo said. “… He would teach me Italian words and phrases and I just became fascinated with it. I felt like I belonged to something really, really cool. Something really, really beautiful.”

Olivo said his grandmother experienced the family history through opera and the arts, while his grandfather associated it with food for the most part.

“There were all these beautiful associations with my Italian heritage that I learned as a little boy,” Olivo said. “And I just, I was fascinated. I fell in love with it and so I made it my goal to learn the language of my ancestors. That was my goal, I was not going to be another typical second- or third-generation American from an immigrant family who had zero ties to their ancestral tongue.”

And in 2003, Olvio got the chance to live out his dream of immersing himself in Italy when he joined the Lazio Ducks (now the Lazio Marines).

A world of difference on the field

When Olivo started playing for Lazio, he quickly noticed a difference. The life he’d lived in the NFL was going to look a little different in the Italian league.

“I was used to a certain standard of football, obviously,” Olivo said. “From facilities, to coaching, to the level of talent, to the fans who showed up on Sundays. I’ll never forget my first game, the guys showing up … Half the team are ripping Marlboro Reds right before the game. They’re hydrating on espresso and who knows what else. But not the normal things I was used to. It wasn’t electrolytes and Gatorade. They were eating prosciutto and cheese sandwiches right before the game.”

“And so coming at halftime, what do they do? Half the teams in, half the teams’ outside again ripping heaters. Like, where am I?” Olivo added with a laugh. “One of my teammates, because I’m kind of coaching and playing at the same time, he says, “Coach, welcome to Italy.”

And while the games were certainly a new experience for a player used to life in the NFL, practices were an even bigger change.

“You’d be fortunate if you had like half your offensive line show up at practice,” Olivo said. “To their credit, if you’ve read the book Playing for Pizza by John Grisham, … the guys literally, they don’t get paid. They basically play for pizza afterward. They all go out to pizza afterward with beer and talk about the game and just create brotherhood. That’s what they do.

“So practice, if you could call it practice, it’s kind of just socializing. The guys show up dressed out. … They practice for an hour and then you go have beers afterwards.”

Olivo was sure to mention that the league has become significantly more organized in the 20 years since he started there. It still exists as the Italian Football League, which played its first season in 1980.

But there were important lessons Olivo could learn. The players weren’t playing to be the best in the world; they were playing because they love football and wanted to.

“It was the time of my life, it was right up there with my time at Mizzou,” Olivo said. “The Italians in the world of American Football, you can imagine because soccer is king, these guys got the leftovers on everything. Facilities, funding, fans, they got nothing. And you would have thought that they were the Dallas Cowboys. They were so happy just to have a helmet and a pair of shoulder pads, even if it was 20-years old and not up to standard. … The footballs, most of the time were rubber. Sometimes they were plastic and may not have even been inflated all the way.

“They were practicing on dirt fields; you were lucky if the game field was a grass field. … There’s probably, 200 or 300 people in the stands, maybe, on a good day. But you don’t even notice it. You don’t notice the crappy conditions, you don’t notice anything because you’re playing the game that you love with the guys you love. And you know what it did for me? It reminded me every day why I began playing football. That was the greatest gift that I walked away from my experience in Italy with.”

A world of difference off the field

While Olivo was playing and coaching his Lazio teammates. He was getting the full experience in Italy.

He traveled, he joined a band, he took lessons to be a sommelier. And he made lifelong friends.

“I could probably write a novella about it with all the experiences I had,” Olivo said. “Four of the best friends that I have right now are my ex bandmates from Rome. They’re all Italian guys. Some of the best meals and adventures I’ve ever had, I had with my bandmates.”

Olivo played rhythm guitar and sang in the band. Though he laughed through the explanation of how he became one of the group’s vocalists.

“The only reason they let me in the band was because I spoke English and they wanted to play English songs,” Olivo said with a full laugh. “I was the only guy that they came across who actually was a native English speaker. Because there were a lot better, a lot better singers out there than me. Trust me.”

Away from the band, but with the team, the world away from the field was different, too. Olivo said the team would bus to games and stop many times along the way on road trips.

“It was a party,” Olivo said. “In Italy, (they have stores) called autogrills. They’re like these road restaurants, and if you want to grocery shop there, you can. You know, charcuterie, the most amazing sandwiches you’ll ever eat, the best coffee in the world. Just everything, unbelievable in these roadside autogrills. We seemingly stopped at every one and got out. The guys lit up their cigarettes, ripped an espresso and talked about everything and anything.”

Beginning his coaching career

After a year as a player with Lazio, Olivo transitioned fully into coaching and began the next stage of his career that has he has been a part of for nearly the past 20 years.

And the same way his start with coaching is a bit unorthodox, the rest of Olivo’s coaching career has been as well.

Most coaches start as graduate assistants at the college level. Olivo’s first full-time coaching spot was as a coordinator for the Bologna Warriors.

But coaching in a league like the Italian League means the focus has to be on more of the basics.

“It allowed me to have patience in teaching the game,” Olivo said. “Because my goal over there was, if I could just help even just one guy become a better football player. It wasn’t about making them fall in love with the game, they were already in love with the game. You don’t sacrifice what they sacrifice to play the game if you don’t love it. But I wanted to really help them improve. So fundamentals, fundamentals, fundamentals.”

Olivo said the coaching was also about helping teach football culture. All the things that go into being a good football player while you’re not on the field.

“The weight room, fall in love with the weight room,” Olivo said of one of his most important lessons to teach. “This isn’t soccer. This is American football. You need body armor. It’s going to protect you, but it’s also going to make you a better football player because you’re stronger and more explosive. You’re going to be able to deliver more physical contact.”

He said there was also a big focus on nutrition and the other outside elements. Because he was confident the Italian players were going to soak it all up.

And after some time coaching one of the league teams, Olivo got the call to be the coach of the Italian National Team.

He said the coaching was an incredible experience with the national team, but selecting the team might have been the best part.

“I got wined and dined in every corner of the country,” Olivo said. “Because every franchise wants you to choose their players. I can only have a 45-man roster of Italian players, so I went around and I would scout. There wasn’t a corner of the country that I didn’t go to to scout. It was awesome. And the team managers and owners would host me and feed me, we’d go to the game and I’d meet all the players and the coaches and I’d make my list.”

“When it came down choosing the final roster, it was difficult. It really was. I tried to approach it in a professional manner and not remember how good that Osso Buco was in Rome or the Linguine Al Tartufo in Tuscany. Or the bottle of Barolo that me and the manager of the Torino team downed one night while smoking cigars,” Olivo said with a laugh.

Olivo coached the national team for a couple of years, as the final job of his extended time in Italy. He said the experience overall was one of self fulfilment and connection with his roots.

“It was a great mix of football and self-realization,” Olivo said. “Cultural diversity all wrapped in one. … I’m able to call Italy a second home, which is really special. My great grandfather wanted to get out of there because it was poverty stricken down south where he was from. And there weren’t opportunities for most Italians from that area back in the day. Now it’s just come full circle. And now his great grandson can actually say that he feels at home there. It’s a pretty cool thing.”

Returning to the US

Olivo returned to the United States full time in 2011, but his unorthodox coaching career wasn’t instantly going to follow the usual path.

He took a job as a running backs coach with the Omaha Nighthawks, a now-defunct team in the UFL. He went on to work for Coastal Carolina (2012-13), the Kansas City Chiefs (2014-16), the Denver Broncos (2017), the Chicago Bears (2018-19), the Philadelphia Stars (2022) and Washington University (2022) before returning to where it all began back at Mizzou starting in 2023.

“My coaching story has not been conventional,” Olivo said. “… For most guys, it’s football, football, football. And it’s all they know from the time they graduate college until the time they retire as a football coach.

“For me, I wanted to be defined as more than just a football guy. Because I knew I had mastered that. I had gotten the most out of my body and my brain that I could for the game of football. And I played at the highest level when I never should have. And I could have played longer, but I left the game because I was ready to do something else. I was ready to turn the page and experience something else in life.”

A chance to go back

As Olivo’s life has returned to the United States full time, he hasn’t forgotten about his roots. In fact, he took a pretty special trip with his father and daughter back in 2018.

In 1918, Olivo’s great grandfather, like many Europeans, made the trek to America in search of a better life.

Exactly 100 years later, the American Olivos got to go back.

“We didn’t know who to contact, but we went to the little town where my great grandfather set off from because my grandfather would talk about it all the time, Santa Severina,” Olivo said. “We went back and went down tot he courthouse and said, ‘Hey, do you have any records on the Olivo family?’”

But as part of the immigration process, the name Oliva, or olive, became Olivo, or olive tree, on Ellis Island. And the American portion of the family was born.

But that left a question mark in the search for the family history because the Olivos had no idea they had been the Olivas.

“You couldn’t script it any better,” Olivo said. “We’re staying in this bed and breakfast just right on the cusp of a little town that’s up on a hill on a mountain and the first morning when we’re having breakfast on the little courtyard, our waiter comes up. He says, ‘We don’t get a lot of visitors from the United States here.’ And of course, he says it to us in Italian, they get zero visitors from the US. He asked us why we were there and I explained, I said, ‘100 years ago, literally, to this year, our relative Vincenzo Olivo, departed from here and went to America. He created a family and now here we are, we’re coming back to pay homage. And we want to know if there are any relatives here.

“He asked for our last name and I said, ‘It’s Olivo.’ He said, ‘Olivo, Olivo, do you mean Oliva?’ I said, ‘Well no, we spell it with an O at the end.’ He’s like, ‘Yeah, yeah, but the family that’s here in town their name ends in an A.’”

After checking to make sure Olivo hadn’t mistook his own name, the coach remembered his time working for the National Italian American Foundation, which promotes Italian heritage and culture in the US. And he recalled how many family names didn’t make it through Ellis Island without change because of the mass of European immigrants coming to the US all at once.

“We had a laugh about that, and the guy said, ‘Dude, I know your family. They’re the town butchers,’” Olivo said.

The waiter offered to take Olivo and his family into town to go meet the Olivas. And what happened next has stuck with Olivo through the years.

“It was a quarter mile away from where we were staying, go figure,” Olivo said. “There’s the butcher shop, Oliva. … We walk in and it was surreal because the gentleman working behind the counter happened to be the owner. His name was Carmen Oliva and he looked so much like a combination between my dad and my grandpa and my uncle. It was just surreal.”

Olivo said he and the family spoke with Oliva and Oliva invited them to his home that very evening. He had even called the family together.

“That very night we found ourselves in Carmen Oliva’s home, his family home with about 40 other relatives who had come out of the woodwork because the Americans had come back,” Olivo said. “It was like a movie. … I thought I was in the middle of a Stanley Tucci, or Martin Scorsese film. It’s just too perfect. We’re looking at photos, I’m translating, my daughter’s there, she speaks Italian. We’re both translating for my dad and his partner. And they’re bringing out these photo books and these photos of my grandfather’s cousin, whose father didn’t immigrate. And they look like brothers. It’s so uncanny how much they resemble each other.

“My dad was getting emotional, it was just amazing.”

The families had dinner together, along with coffee and desert to get the full experience.

“They were just elated that we had taken it upon ourselves and it was important enough for us to come back and rediscover our roots,” Olivo said. “Just an amazing experience. My dad will talk about that until his dying day. It’s one of the best experiences he’s ever had.”

A well-rounded life

Olivo sought to have more than football in his life. And he has.

He has learned multiple languages, lived in a foreign country, discovered his ancestral home, danced the argentine tango, took a class to become a sommelier, played in a band, and met a lot of people through all of it.

“You meet interesting human beings along the way who can leave nothing but an indelible mark on your life,” Olivo said. “There’s always something to glean from these people along the way. The more people you meet from more diverse backgrounds and cultures, the more rich you’re going to be as a person.”

Olivo said that was the goal. To become rich in experience and life lived before he returned to football.

But now he’s back in Columbia as a different person than the one who left to go to the NFL in 1998. One who has absorbed life and learned many lessons.

“I think having a balance makes you much better at anything you do than if you’re just tunnel visioned and sort of short sighted,” Olivo said. “So that’s my approach and I credit my mom and my dad for giving me that outlook.”

But through it all, Olivo knew he wanted to stay around football. Especially once he had lived the life he wanted to outside of the game.

“I knew that I would come back to football, because that is my No. 1 love,” Olivo said. “That’s my No. 1 passion. I wanted to be involved in the game of football, I wanted to coach the game of football. I wanted to give back to the game what the game has given me, even though I could never do that. The game gives you so much more than you can give back. But I wanted to do that, and I knew I would be a better coach and a better teacher if I went out and became a more dynamic human being.”