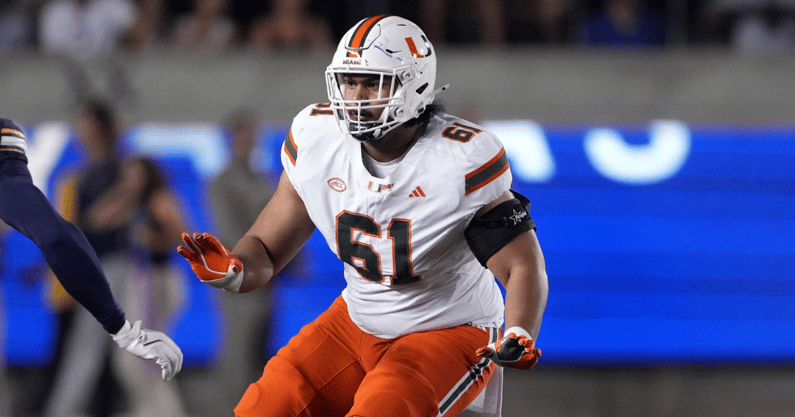

Faith, Family, and Football: How Francis Mauigoa’s Samoan Roots Shaped a Miami Hurricanes Star

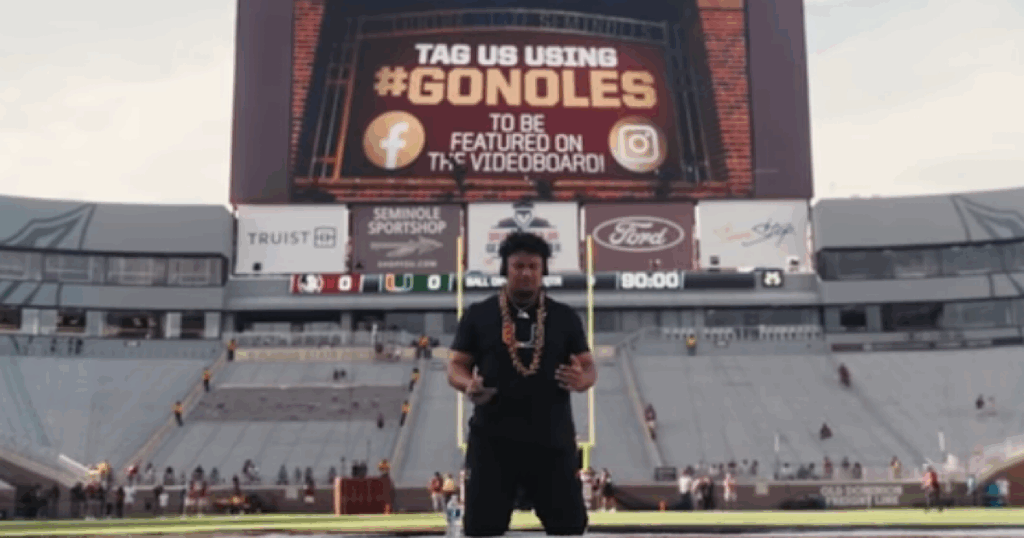

Under the floodlights of Hard Rock Stadium, the noise fades for just a moment. Before the captains meet at midfield, before helmets clash and voices boom, Miami Hurricanes offensive tackle Francis Mauigoa kneels alone.

Six feet, six inches tall and built like a fortress, the junior lineman folds gently to the turf, his hands stretched open, his eyes closed, his head bowed in reverence. Worship music hums through his headphones, his own private cathedral in the middle of chaos.

“I’m always putting God first because God put me in that position to do something,” Mauigoa said. “I feel like God has a calling on my name with football, and I wanted to use that platform to glorify His name.”

It’s a ritual. But more than that, it’s his identity. Moreso than even his presence as a football player, one of the best offensive tackles in America, a sure bet to get drafted in the first round of the NFL Draft next April.

Every prayer before kickoff is a whisper to home, a place where faith and family are woven tight.

Thousands of miles away, on a small island in the South Pacific, the evening air of ‘Ili‘ili, American Samoa, carries that same reverence.

At six o’clock each Sunday evening, the village grows still. Shops shutter, radios turn down, children hurry indoors as the call of a conch shell and church bell drifts through the humid air. It signals Sa—the sacred hour of prayer. Families gather around tables, and neighbors visit one another’s homes because, there, faith isn’t practiced alone. It is the living foundation of Samoan community.

“There’s a saying that, you know, it takes the whole village to raise a kid. I feel like my whole village took part in that,” Mauigoa said. “Everybody knows each other, and everybody takes care of each other.”

He remembers bouncing from house to house after school, a big-hearted, bigger-bodied boy, welcomed everywhere he went for a meal—not out of need, but out of belonging. “Every family still treats you like their own,” he said. “They see you as their own kid too.”

In ‘Ili‘ili, population barely 3,000, Francis “Sisi” Mauigoa grew up surrounded by love and scarcity in equal measure. There was little money, little infrastructure, little exposure to the world beyond the ocean horizon. But there was abundance in the things that mattered: faith, love, and family.

He loved football before he even knew what it truly meant. Before the 6-foot-6, 300-pound lineman was one of the most recognizable faces on the University of Miami’s roster, he was just Sisi — a boy with big dreams and no football field. Equipment was scarce. Opportunity, even scarcer.

“I had to make my own equipment and everything,” he said. “Back home, I used to cut slippers to put them on as kneepads. Some kids shared it just to get into the game… So looking back at those times, I mean, that’s what makes me take advantage of every opportunity that I get around here.”

In American Samoa, football isn’t just a sport. It’s a dream carried by nearly every boy with a ball in his hands. According to CBS, the islands produce more NFL players per capita than any place on Earth. But for kids like Sisi, separated from the continental U.S. by 4,800 miles of ocean, opportunity felt mythic. The first youth football league on the island didn’t even exist until 2011. Practices were played on uneven, overgrown fields with hand-me-down gear and taped-up helmets.

Then, at 14, came his turning point.

Keiki Mesipeka, now a member of the University of Miami’s personnel staff, arrived on a scouting trip to Samoa. When he met the Mauigoa brothers, Francis and recent Miami linebacker Francisco who now plays for the New York Jets – he saw raw potential wrapped in humility and heart.

“We figured, staying back home, we’ll get nothing out of it. We don’t have exposure. We don’t have film to send to college. We didn’t have nobody come to visit us because we were far away from the mainland,” Sisi said. “So Coach Keiki came up with an idea to send us over here to California.”

It was a decision that rippled through the community. In Samoan culture, children rarely leave home before marriage. Family is the nucleus of life, the basic unit of society. Elders are revered, faith unshakable, and distance between loved ones is almost unthinkable. But when Sisi’s parents, Telesia and Fa‘alialia, heard their son’s dream, they placed their faith where they always had.

“I was able to let him go into God’s hands, knowing that he will provide and guide as well as protect,” Telesia said. “We prayed a lot about it. As God being the Redeemer and the provider, He gave us the answer.”

So, with a couple bags and a heart full of excitement, uncertainty and faith, a 14-year-old boy left everything familiar behind for St. Thomas Aquinas High School in San Bernardino, California.

The leap from ‘Ili‘ili to California was like stepping into another planet—new language, new customs, new expectations. The air was drier, the crowds louder, and the competition relentless. But Mauigoa carried something that couldn’t be coached: a quiet fire born of gratitude, strength and humility, forged in Samoa.

“You know, my team is my family. I’ve grown to know that my team are my brothers,” he said. “I can’t be the weakest link… I have to earn my brothers’ respect to be on the field.”

That sense of brotherhood, first learned in his village, became his compass in America. While other players talked trash and chased attention, Mauigoa led by stillness. He doesn’t talk back to the coaches or to his teammates. His mother says he respects everyone young and old. It was the way his father taught him, to listen before speaking, to serve before leading.

Every game day, the ritual repeats itself: the music, the prayer, the moment of surrender. Samoa’s national motto, Samoa, Muamua Le Atua meaning, “Samoa, let God be first,” is etched on his heart.

“It’s a constant reminder here at home that we give to our boys. Never forget God, because without Him, none of this would all be possible,” Telesia said.

Top 10

- 1New

Vanderbilt field storm

SEC announces fine decision

- 2Hot

More sign-stealing?

Lane Kiffin singles out OU

- 3

Bryant Wesco injury

Dabo Swinney reveals severity

- 4Trending

DJ Lagway

Addresses his future at Florida

- 5

Mike Elko

Shreds media over PSU question

Get the Daily On3 Newsletter in your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

Even oceans couldn’t weaken the bonds. When Francis left home, the calls came whenever possible. But the absence was heavy. Samoan culture thrives on presence, community, the subtle language of hugs, shared meals, glances that say what words cannot.

When Francis signed with Miami in 2023, everything came full circle. This time, his parents came too. Through his NIL earnings, Mauigoa retired his mother and moved his family to Miami—a gesture that felt less like triumph and more like restoration and purpose.

For them, the occasional phone call, though acceptable in Western culture, wasn’t enough. Being physically with each other brought a sense of home to a new place.

“With the physical part of it… You will see, you know, just by looking at their eyes. You could tell so much that’s going on. That’s another good thing about us being here, is to witness all that,” Telesia said.

The Mauigoas are a presence at practices now—smiling from the sidelines, waving, offering food and encouragement to any player who needs it.

“During practice days, we will come and participate and witness him in practice not only for him, but for other kids as well,” Telesia said. “I know there are some kids on that football team that maybe, they’re going through the same thing that we went through. Those little statements go a long way for someone whose parent is not close by.”

From the barefoot boy who cut slippers into kneepads to the dominant tackle now anchoring Miami’s line, Mauigoa’s story feels almost mythical. But to him, it’s simple: faith opened the doors, family held them open.

Now a junior, he’s projected near the top of the next NFL Draft and is on the watch lists for the 2025 Jason Witten Collegiate Man of the Year Award and the Polynesian College Football Player of the Year Award, an honor that carries the weight of his culture.

“You know, being a Polynesian player of the year means a lot to not only me, but for our people,” he said.

That’s because it was never about the spotlight. Never about money, glory or grandeur. It was always about giving back to the same village that once gave him everything.

“There’s kids out there that get lost because nobody ever sees them,” he said. “Whenever I feel tired, that’s when I think about, you know, those kids back home that want to play football.”

One day, alongside Francisco, Sisi plans to open a football facility in ‘Ili‘ili—a place where dreams can grow without leaving home.

“My pride and our culture, I mean, that’s just who I am. That’s my identity,” he said. “I want to let people know who I am… it’s better for me to show it rather than telling them about it.”

And so, every Saturday before he goes on the field to dominate for the Hurricanes and when he kneels to pray, the echoes of ‘Ili’ili still reach him — the call of the conch shell, the sound of hymns drifting through humid island air, and a village that once raised a boy who would never forget where he came from.