The Story of Ricky Lanier: Trailblazer, Record-Holder, Tar Heel

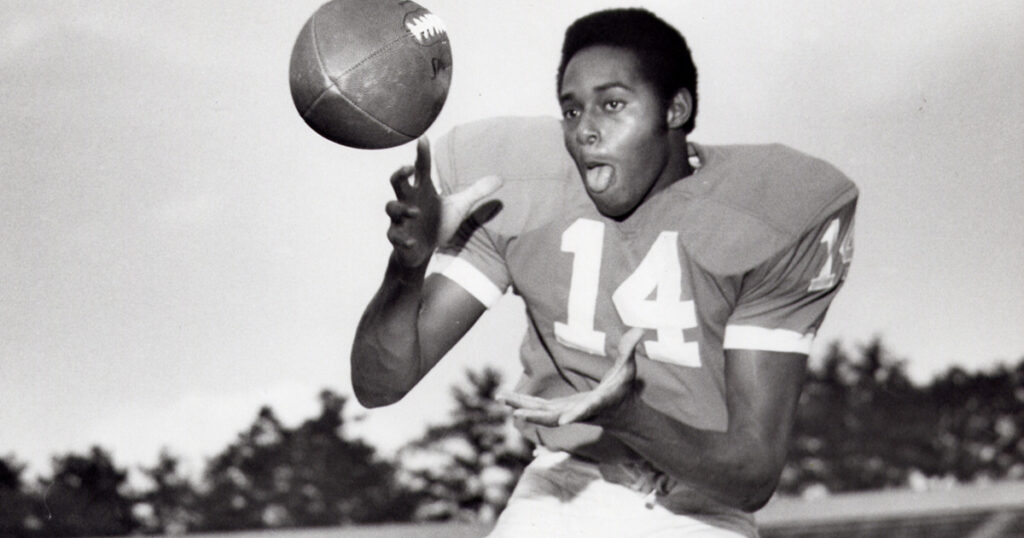

Ricky Lanier, the first black scholarship football player in Carolina Football history, died earlier this month at age 76. The following article about Lanier was originally published in the November 2014 issue of the Inside Carolina Magazine, highlighting Lanier’s time at UNC, and his performance that still stands atop the record books today.

By Matt Morgan

Ricky Lanier bounces down the sideline at Kenan Stadium. It’s about an hour before kickoff of the North Carolina vs. San Diego State football game. He’s wearing a black hat and shirt, representing one dot of one of the stripe portions of the Stripe Out fan promotion he’ll join when he makes his way up to his seat about 20 minutes later.

The former quarterback is recognized by some. Ricky calls them old-timers. A few fans, a ticket taker on the way in, ushers who know who he is and his relevance in Carolina football history. These people mean so much to him, he says. He sometimes thanks people for remembering his accomplishments, in a way that’s genuine and endearing instead of self-serving the way some might say it.

Despite the occasional knowing glance or handshake, Ricky is largely anonymous in the speckling of black on the field at his alma mater. It’s not like he’s Charlie Scott at a basketball game, but at the same time that’s exactly what he is.

The hips that could once shake the spare change out of defender’s pockets, are gone. Well, one of them at least. The Williamston, N.C. native had a hip replaced in 2007, and four decades since his last game at Carolina that artificial hip seems to be the only thing keeping his essence from escaping back onto the field.

Lanier bursts with energy. He breaks into laughter about three-quarters of the way through most sentences, whether what he’s saying is funny or not. He laughs with an earnest conviction that makes you reconsider what he said to make sure you didn’t miss the joke. You didn’t. Lanier, now a high school science teacher in Greensboro, just gets a kick out of the next word, next day, next week, next year.

“Why do I still go back?” Lanier repeats. “Number one, I love our University. I love that place. They brought me back as a trailblazer last February. That was by far one of the biggest events in my life. To be recognized by your university as a trailblazer, along with Charlie Scott and a couple of other young ladies. That place, I just love Chapel Hill. I love the University of North Carolina…

Tonight, there’s a special energy in the stadium. You can tell football still gets Lanier revved up. He comes to all the home games, but this nationally televised game takes it to another level. Lanier ends a phone call saying “Take care and go Heels” like it’s a secret handshake. Later, he heads to his seat and prepares to watch a black quarterback, Marquise Williams, start for his university 47 years after he was the first black scholarship football player in school history.

Lanier doesn’t dwell on the topic of race. He knows people don’t exactly believe him when he says he didn’t encounter pushback when he came to UNC in the 1960s, but he insists it’s the truth. When you have a group of people all fighting toward the same goal of winning, he says, there’s no room for race. “There really isn’t,” he repeats.

This might be Lanier’s positivity affecting reality. It might not. But it’s the only version of the story he tells.

“It was no big deal,” Lanier says. “When I finally took the pictures (signing), it was gone in an instant and I was ready to play football. The studying to stay eligible and all that stuff. There’s a lot of things you have to do to play college football. You’ve got to train. You’ve got to go to class. You’ve got to keep your body in peak condition and you’ve got to study your opponent. There wasn’t time for (race). There wasn’t time for it. Even though this was during the civil rights movement. I was doing my plight by coming to the university of North Carolina, which I love.”

Even so, it’s hard to ignore the significance of Lanier watching Williams not only start, but play quarterback this season. He and Williams aren’t all that different. Both are North Carolina natives. Both are/were fast, though Lanier probably more so. Neither gets enough credit for their arm, though Williams is a more accomplished passer.

Lanier has a second stake in North Carolina history. In addition to being the first black scholarship football player at UNC, Lanier is also the single-game record holder for rushing yards by a quarterback with 174, a number he set in just three quarters.

“ONE-NINETY-NINE. ONE-NINETY-NINE,” Lanier quickly corrects. “My parents, God rest their souls, said it was 199, the record that day that I ran for 199 yards and they said I got caught behind the line and I lost it, but I ended up with 199. So, I actually had a lot more than 199. I don’t know how you can be sitting in the same press box and get total rushing yards (different).”

Remember the people at Kenan Stadium who recognize Lanier at football games? UNC athletics communications staffer Kevin Best is probably one of them. Lanier doesn’t talk to him this night but he has on other occasions, claiming the total for his rushing record has changed a few times in the media guide since the 61-11 win over Virginia Military Institute in 1969.

Newspapers at the time reported different numbers—174 and 154—and mention Lanier having passed teammate Don McCauley’s single game record of 188 but, as Lanier confirmed, say he lost yardage late in the game which dropped him back behind the record-setting mark. Carolina currently has it set at 174, which when viewed in context of the newspapers seems right. But that doesn’t mean it is.

“How do you lose yardage sitting at home?” Lanier says with a laugh and slightly feigned exasperation. “Kevin says, ‘I’m not touching that, that was too long ago.’ But I just let it be. If Marquise Williams has a day and breaks that record, I’ll be the first one down to congratulate him.”

XXX

First, you have to understand that Ricky Lanier was going against servicemen. They were respectable men who helped him up after he was knocked down and complimented him on his better runs. These were men you wanted to best but not embarrass.

Second, you have to understand, Ricky Lanier was in the freaking zone. When you were a highly recruited high school quarterback who threw for 41 touchdowns, who now had to split time between quarterback and split end and kick returner and ball holder on extra points in college and you get the chance to play quarterback and you’re in the freaking zone, you go with it. Even if the Dalai Lama is playing safety for the other team, you stutter step and beat him to the corner.

In 1969 that was the situation Lanier was in. UNC played three different players at quarterback that season, Lanier, John Swofford and Charles Turco. Lanier remembers starting the game but it’s unclear whether that’s accurate. What’s certain is that Swofford got most of the snaps in the first quarter and, after falling behind 3-0 to VMI, helped Carolina score 34 unanswered points. McCauley ran through the porous VMI defense, racking up 125 yards in the first quarter. Early in the second, McCauley scored his third touchdown and, along with most of the first unit, called it a day. Lanier then entered (or re-entered) the game on Carolina’s next drive with the rest of the second unit to seemingly turn on cruise control against the Keydets.

Instead, Lanier quickly realized he was the fastest player on the field and beelined for the record books. Running what today, Lanier says, would be described as the read option, the 6-foot 176-pound quarterback ran wild on VMI for the final three quarters.

With an All-American back like McCauley, the read option was almost impossible to defend when run properly. Defenders had to respect the bruising back, and the moment the defensive ends and backs committed to McCauley, the quarterback could take off.

“We would fake the ball and leave the ball in the tailback’s belly for a long time, almost all the way into the line, then you would take it out if the defensive end crashed down and tried to tackle him,” Lanier explained. “At that point you would run right by the end and by that time I guess I was fast enough that I was already running down on safeties because the cornerbacks and all those other guys were already crashing down.”

Top 10

- 1Hot

Latest Offseason Scoop

Intel on start of portal season

- 2

Defensive Lockdown

Heels rout Hoyas

- 3

Portal Tracker

Who's leaving?

- 4

Rob's Takeaways

'Those days are over'

- 5

Meet the Class

UNC's 39 signees

Get the Daily On3 Newsletter in your inbox every morning

By clicking "Subscribe to Newsletter", I agree to On3's Privacy Notice, Terms, and use of my personal information described therein.

Even with McCauley on the bench in the second quarter, the belly series worked flawlessly. Lanier had run the offense during a high school all-star game a few years before and had long been an admirer of Fayetteville native and Michigan State standout quarterback Jimmy Raye. He had a great feel for when to hand it off and when to take off and this was his magnum opus.

With 3:30 left in the half, Lanier broke loose for the first time, keeping the ball on a sweep and running 61 yards for a touchdown, giving UNC a 41-3 lead. Lanier nearly scored again before the end of the half, stumbling over his own feet after getting past the final defender and having to settle for a 37-yard gain.

In front of a homecoming crowd of 29,500 fans on an overcast day, Lanier finished with (about) 174 yards rushing and 10 completions for 136 yards. The 61-point total was the most Carolina had scored since a 61-0 win over Virginia in 1935 and the 675 yards of total offense was a school record.

The Yakety Yack claimed Lanier lost the record on the last play of the game, but Lanier doesn’t remember that at all. A loss of (a minimum) of nine yards on the final play of a blowout also seems unlikely. Forty-five years later, it doesn’t really matter. Even to Lanier.

“It was just a fun time for me,” Lanier said. “I had no idea there were any records involved at all. You just get in the zone sometimes and I knew I was in a zone and I kept it going.”

XXX

There were times that were trying at Carolina, Lanier says, but they were infrequent. Early in his career he, Charlie Scott and teammate Jim Webster went to the chancellor to ask him to prohibit the playing of Dixie during football games. The chancellor respected the request and the practice ended. It was mostly things like that, Lanier says.

“I never got any, ‘Oh, you shouldn’t be here,’” Lanier says. “I never had a problem in Chapel Hill. I never had a problem at the University of North Carolina. If there were people who did (have a problem), they kept it to themselves.”

Today, Lanier teaches science at Western High School in Greensboro, N.C. where he discusses topics like the environment and conservation with young people. He worked in corporate America early in his career but after his parents, both of whom were career teachers, died in a car accident, he felt the urge to come home from California and honor them by becoming a teacher.

“I enjoy giving back. I enjoy helping students,” Lanier says. “I enjoy seeing them when the light goes on when they ‘get it.’ I try to help them not make mistakes and look at life realistically. I enjoy being a high school teacher.”

Distractions abound in a high school classroom in 2014 but he says kids aren’t any harder to reach now than they were when he was in school. If anything, the technology allows you to challenge them more.

“Kids learn from anybody they know that cares about them and they can tell if a teacher doesn’t care about them,” Lanier says. “I care about all my students. Whether it’s buying them lunch or helping them with a problem or listening to them when there’s something they’re having difficulty with. When a student knows you care, they will learn.”

Lanier doesn’t talk much about his Carolina days to his students, in regards to his status as a trailblazer or his rushing record. He doesn’t want to come off as a self promoter. He does more listening, he says.

That doesn’t mean he’s not proud of his time at Carolina. That’s why he loves going back and watching guys like Marquise Williams grow and learn and enjoy a special time in their life. A time many don’t fully appreciate until they are much older.

“They won’t realize how fortunate they are until they get into their 40s and 50s, until they mature,” Lanier says. “While you’re young and you’re maturing, all you can think about is tomorrow and think you’re immortal, but when you get old enough to realize that your physicality isn’t what it used to be or that you’re on the other side of that—you start appreciating the opportunities and the place you went to college, like I did. I loved the University of North Carolina.”