Musings from Arledge: Psychology, Momentum, and the Turnaround

“You can’t always get what you want. You get what you need.”

–The Rolling Stones

There was a time – not too long ago – when the holiday season was a joyful time for USC football fans. You had Christmas, New Year’s Eve, and then the thrashing of some hapless Big 10 victim in the Rose Bowl. It was great, consistently great, so great, in fact, that it became not so great anymore. Some USC fans simply got bored of it. We began to complain about top-5 finishes and Rose Bowl wins because there was no national title to celebrate. (Of course, had there been a playoff….) What a wasted season, we thought. Pete is letting the program slip, we said.

We were spoiled. We were engaged in the type of thinking that Nick Saban railed about recently. It is beside the point that Nick Saban can deliver such a rant without also recognizing that it’s exactly this type of spoiled, lack-of-perspective football love from the fans that allows him to live here.

Yes, Nick, fans that care too much develop unreasonable expectations. They also put you in a pad that Robin Leach might tour had he still been alive.

Nick Saban is not the victim here. But he’s right to warn us of this attitude, for it always brings with it something awful, a “reckoning” as Val’s Doc Holliday might put it. It brings the wrath of the college football gods.

So we got what we needed, or maybe just what we deserved: a solid dose of the best attitude-adjustment medicine the college football gods have to offer. We got coal in our Christmas stockings for the better part of a decade. Yes, there was an occasional triumph – thanks, Sam! – but those were the exception. What we really got, by the barrel full, was regular-season buffoonery followed by bowl ineligibility or votes not to play or second-tier bowls for which the team doesn’t even bother to practice followed by off-seasons full of empty promises but empty of any real hope, because we could all see that the same clown car was still parked in the best parking spot near Heritage Hall.

Now, sufficiently chastened, we have been given hope again. And the big question for all of us is: how long will the turnaround take?

Lincoln Riley has surprised me on this. I would have expected him to try to extend the honeymoon by talking about how it could take some time, many years even. Nobody who watched USC play this year would have been surprised to hear it. That was a depressing, grim season. Saw was more uplifting. Or Riley might simply have dodged the question entirely the way Pete Carroll did, who answered, “We’ll be good when we’re good.”

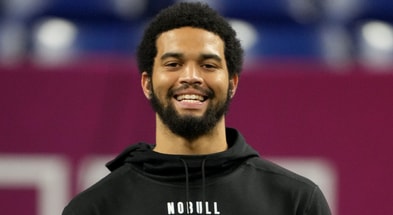

But Riley has been bold and tells us it can be done quickly.

It wouldn’t be unprecedented. First-year turnarounds do happen in college football. Urban Meyer took Ohio State from 6-7 to 12-0 in his first season. June Jones took Hawaii from 0-12 to 9-4 in his first season. Even Steve Sarkisian had a five-game improvement at Washington, which went from 0-12 to 5-7 in his first season.

(There are others; look them up. Having come across Sark, I no longer have any appetite for the research. But, please, reach out to a Longhorn fan in your life. They need some holiday cheer right now.)

Often these quick turnarounds happen because the previous season was so unusual. When you have an outlier of an outcome (good or bad), you would expect some reversion to the mean. Washington is not a program that usually goes 0-12. That result was an outlier. You would expect Washington to bounce back to a season closer to its historical norm. And Sark obliged, taking Washington from horrific to mediocre in short order … and then camping out there for an extended period of time, of course, mediocrity being Sark’s favorite place to hang out.

The same was true of Ohio State, where 6-7 seasons are spotted less frequently than sasquatch. You would expect Ohio State to bounce back to a decent record no matter who arrived to take over the team; that the new coach was an all-time great just made the ascent that much faster.

What the “mean” is that you revert to depends on the player and on the program, of course. If Kobe goes for 81, you couldn’t possibly expect that he’d repeat that the following game. He’ll likely revert to his mean, something in the high twenties, Kobe’s mean being well above the NBA mean. Ohio State has a mean much higher than Washington’s or Hawaii’s. Ohio State should win nine games a year when it’s doing nothing special. Washington is probably closer to seven.

USC has the highest mean in the Pac 12. For USC, a 4-8 season is an anomaly. No, it’s wasn’t an anomaly that USC played poorly. Under the ancien régime, warriors weren’t really trained to do things like block or tackle. Expectations were low, like the attendance.

But 4-8? That’s unusual at USC, where it takes a whole series of strange occurrences, including coaches who were completely checked out and a large number of players who seem to have quit, to crash into a gully that deep. You’d expect USC to bounce back to a more normal record in 2022 regardless of who was hired to coach. And if you replace the old staff with a highly competent staff – which they have – then a gain of four of five wins in the first year isn’t unlikely at all.

It could be even better, because this highly competent staff has something that Pete Carroll and John McKay did not: the transfer portal. Lincoln Riley will turn over the USC roster in ways that his predecessors could only envy. USC will not have Alabama talent on the roster next year. But I suspect it will have a very solid roster, a very manageable schedule, and one of the great offensive coaches in the country directing a pretty high-powered attack. Next year’s team should compete for the conference title.

I think. I hesitate only because the more difficult thing to predict is how long it will take to change the culture of the program. By this, I don’t just mean raising expectations and demanding hard work. That happens on day one, and any players who don’t seem to fit in with the new expectations have been given or will receive the college-football equivalent of a pink slip.

But there’s something else that needs to change, and it might take longer.

Psychology.

There was an interesting article on ESPN.com this week about momentum and whether it really exists. I think it does; not as an outside force that can deliver power to one team or another. You can’s harness momentum like the Force to throw passes or blocks with Jedi powers. I think momentum is mental, but its effects are no less real. And USC football has some negative momentum that needs to be addressed.

There is a well-known little book in coaching circles – Pete Carroll, Steve Kerr, and Phil Jackson are all fans – called The Inner Game of Tennis. The great insight in the book is one that is also discussed from a different angle in a couple of other very important books, Thinking, Fast and Slow and The Righteous Mind. In essence, all of us have two minds, two selves really: the logical and the intuitive. And the logical brain is a terrible athlete. The Inner Game of Tennis describes how the logical brain – always thinking, always criticizing, often worrying – gets in the way of peak athletic performance. It is the intuitive self that leads to athletic success. This poses certain problems for a coach, who interacts with players through logical instructions – if you want to block better, put your hands here, lower your base, etc. These are logical commands that require a player to think about what he’s doing and try to implement changes. But the thinking brain and the intuitive brain are not the same. Only when an athlete no longer has to think about something can he do it well and do it consistently.

This is why you so often see athletes do something well in practice and fail in a game. In practice, there is no pressure. The athlete can simply do what comes naturally, and it works. He doesn’t have to think. He doesn’t worry. But when the lights are bright, the athlete is unable to just relax and do. He starts to think. He starts to worry. He invites the logical brain to meddle and interfere.

This is why even the greats sometimes choke under pressure. A thinking player is a failing player. Players “in the zone” never think. Things just happen. The intuitive brain takes over, and the muscle memory from thousands of hours of practice allows the athlete simply to perform.

What does this have to do with momentum? Everything, I think. Players and teams who are used to success believe they will be successful. Kobe Bryant and Michael Jordan expected to hit a game-winning shot. It doesn’t mean they always did. They both missed plenty of big shots. But because of their history of success and their mental makeup, their logical brain wasn’t filling them with doubts. And because the logical brain wasn’t interfering with their performance, they could shoot a jump shot at the end of the game exactly the way they had shot them in practice on thousands of occasions. They were free of the shackles of the criticizing, worrying logical brain.

So when Kobe or Michael would heat up, two things would happen. First, they played with extreme confidence. There was no concern, no worry; it was all just the muscle memory of trained greatness. But for their opponents, the effect was the opposite, and thus the second thing would happen: the other team would get tight. They’d press. They’d be thinking about what they needed to do to stop Kobe or Michael from scoring. And the more they’d be thinking, the more the logical brain was interfering, the less effective they could expect to be. Things would simply get worse.

Entire teams can benefit or be victimized by this phenomenon. I’ve felt it myself many times. But the one that stands out is a story of failure, not success. (Naturally. As long-time readers should know by now, I am something of an expert in bad teams, having played a prominent role in so many.)

My senior year in college, our team was awful. We were losing every week and getting blown out most of the time. Toward the end of the season, we had a road game in Iowa on a brutally cold day. We played well, surprisingly so. The defense was getting stops. The offense wasn’t turning the ball over. And late in the fourth quarter we led by a score. Our offense just needed another first down to put the game away. They couldn’t get it. We punted, and our opponent started around their own 35 or 40. Keep in mind, we had been shutting this team down virtually all day. Our defense had reason to be confident.

But it felt tight in the huddle. We really needed this win, and we knew we needed one stop to get it. And then things got worse. The first play was a short pass for a first down, and the receiver got out of bounds. The second play was the same. And at this point, you could feel the doubt. I felt it in myself, and I could see it in my teammates. I tried to fight it. I wanted to believe we would win. I continued to try to talk myself into it – bully myself, might be more accurate, since the persuasion I was attempting was not at all subtle.

But the doubt from a season of losses was a lot to overcome. We started to overthink, and that made us react slowly. We weren’t breaking on the short passes as quickly as we had been early in the game, because we knew the stakes and were scared to get beat deep. With the help of no pass rush, poor secondary play, and a pass interference call, our opponent drove the length of the field. With seconds left, they won the game on a short fade route where the ball cleared my outstretched hand by no more than a couple of inches.

Don’t tell me momentum isn’t real. There was momentum at the end of that game. I could feel it. But the momentum was not something that existed outside of us. It was in our heads. It was the psychology of recent failure, made worse by a pressure situation, the pressure of trying to make a play when we so badly wanted to make a play, of trying to salvage a Titanic of a season with one magnificent last stand.

USC will be well coached next year. USC will have plenty of talent to match up with any of the teams on the regular-season schedule. I suspect the guys who remain on this roster will be motivated, will work hard, and will have bought into Lincoln Riley’s system, and it’s a good system.

But it’s hard to overcome the disappointment and embarrassment of the last few seasons, and especially of 4-8. The speed of the turnaround will be dictated not just by the roster turnover, but by the psychological turnover. The question is how long will it take before the recent history of failure, the memories of bad losses and empty stadiums and booing fans, will go away. Because until it does, USC will always be playing with the ghost of seasons past constantly telling them that things are about to go south. And those voices have power.

It was after USC’s win against Arizona, in the middle of his 6-6 inaugural campaign, that Pete Carroll told his team, “We don’t have to lose anymore.” USC doesn’t have to lose anymore. The big question is how long it will take the players to truly feel that when it matters. If they learn that lesson quickly, so they can simply relax and leave the past in the past, the turnaround will happen in season one. And if not, at least we still have hope – and as Red tells us, hope is a good thing, maybe the best of things.

Another year down. They go so quickly now. It’s been a pleasure to be part of WeAreSC for another year. I enjoy writing this column and doing the Inside the Trojans Huddle show, and I appreciate the people who make that possible. So thank you to Greg, Scott, Marc, and Kevin. And thank you especially to Erik, who lets me do what I want here with very little interference yet still manages to keep me from indulging in my worst excesses. (Yep, the original columns are often even worse than what you read.)

Thank you to the Trojan fans willing to actually read this column and comment on it and occasionally reach out to me.

And thank you to Carol Folt, Rick Caruso, and Mike Bohn – I wasn’t sure I’d ever write that! – for bringing hope back to Troy. Now Musings can come full circle, from prophet of doom originally to bitter enemy of the status quo during the middle period to, now, sunshine pumper. And the sunshine feels good.