Carl Snavley’s Dye Tie: When Blue Baby Syndrome Weakened the Baby Blues

Usually when a coach makes the bold move to poison an entire roster of football players just days before the biggest rivalry game of the season he does it to the opposing team, not his own.

First-year North Carolina coach Carl Snavely went the other way, derailing what might have been the most remarkable debut season in UNC-CH history because of a freak accident that turned his own players blue and threatened to cancel the annual rivalry game against NC State on Oct. 27, 1934.

Snavely, recently hired from Bucknell, posted shutouts in the team’s victories over Wake Forest, Georgia and Kentucky in his first four games. Its only blemish was a 19-7 loss to Gen. Robert Neyland’s Tennessee Volunteers in Chapel Hill.

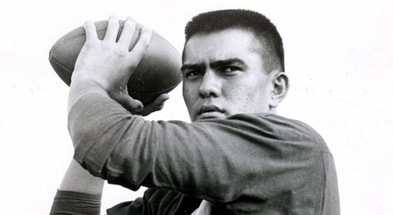

Led by two-time All-Southern Conference and All-American linebacker and guard George Barclay, the Tar Heels had a talented team that underperformed in previous seasons under Chuck Collins. Snavely changed the culture at the school. (In 1935, he had the Tar Heels in perfect position to be the first team from the Old North State to earn a bid to the Rose Bowl, until a late-season loss to Duke.)

With strong players and a good coach, the Heels had a decent path to win its final five games.

NC State was also under the guidance of a new leader, former Notre Dame head coach Heartley “Hunk” Anderson, who was hired to produce a program that could challenge the school’s rivals in Chapel Hill and Durham.

His debut season started fine, with wins over Davidson and South Carolina, but it was clear he did not yet have the Fightin’ Irish system in place to be successful just yet.

The Tar Heel faithful, coming off what the UNC student newspaper called “the greatest upset in the history of college football” against Georgia, believed Snavley and his charges would roll over lowly State College.

That’s when chemistry came to call.

On the Wednesday before the game, Snavely gave each of his on-time players new practice jerseys, with freshly painted numerals from the student laundry, as a reward for back-to-back wins over Southeastern Conference opponents.

The eager players put them on when the aniline dye used for the pretty dark blue numbers was still a little moist. Fully dried, the synthetic dye caused no ill effects. When wet, however, the crystalline version of indigo could be absorbed into the skin, causing fingernails, lips and skin on hands to turn a freaky color of blue, not from the dye bleeding from jersey to skin, but from the early effects of methemoglobinemia, or “Blue Baby Syndrome,” a known symptom of exposure to aniline dye.

Snavely later blamed the dye for why his team stunk up the field against the Wolfpack – quite literally, in fact, since the lingering toxic aniline base was known to smell of rotting fish.

The crisis began with when Tar Heel upperclassman Lex Moser walked through the door of the infirmary with a laceration above his eye, an injury that only needed a few stitches. But the on-duty doctor was horrified to see Moser leaking dark black blood, a macabre sight less than a week before Halloween.

As campus physician Dr. Reece Berryhill came in to see Moser, he saw more than a dozen other Tar Heel football players lined up against the wall in various stages of distress and various hues of the school color.

“Their faces were blue, so dark as to be almost black, and I can tell you it scared me,” Berryhill told the Daily Tar Heel. “For a moment, I thought they were dying.

“Then they began to talk and laugh, and I knew they couldn’t be as bad off as they looked.”

After dinner, more players from the team visited the infirmary, about 40 in all. The only two players on the roster who didn’t get sick had been late for practice and didn’t get new jerseys as punishment. After interviewing the players, the school doctors came up with the following assessment, all of which was likely gathered from research done at NC State’s world-leading School of Textiles:

“The squad had gone on the field that afternoon wearing practice jerseys on which numerals had just been stamped with ink of a type that is regularly used at the University laundry,” the school paper reported. “When dry, the ink is harmless; but the players had put their jerseys on before the ink had time to dry, and the dye was absorbed through the skin into the bloodstream. The players showed signs of the poisoning soon after the close of practice, but the full effects were not evident until they had finished supper.”

For the next two days, the symptoms of nausea, paleness, headaches and dizziness persisted because of the dye poisoning, but the blue color faded as physicians prescribed heavy doses of soda as an antidote. Early reports said that as many as a dozen players would not be available to face the Wolfpack and the game might have to be canceled.

It was a busy week for the UNC medical staff, as it had quarantined an entire fraternity over a scarlet fever outbreak. The school arranged to broadcast the State-Carolina game to the fraternity house with a rare radio play-by-play. (Eighteen years later, the State-Carolina game was canceled because of a polio outbreak in Chapel Hill, the last time the two teams did not play an annual contest.)

“They battle on even keel in a game that is apt to produce anything—and usually does,” wrote Raleigh’s News & Observer the morning of the game. “When Anderson took over his duties in January, he jokingly was told that if he could beat North Carolina in the fall he could have a life-time contract. He makes no secret of the fact that he has been pointing his Wolfpack for the North Carolina game.

“Snavely has faced a heavy schedule at North Carolina this fall and has done a good job as the Tar Heels’ defeat of Georgia and Kentucky indicates.”

At the time of the 27th meeting of the two rivals, North Carolina had 19 wins, State had three and there were four ties.

Hours before the 2 p.m. kickoff, however, UNC team doctors cleared everyone on the roster to play and said they would not be affected by their symptoms.

That apparently was not the case in Snavely’s eyes, because his team played listlessly all afternoon in front of the Homecoming crowd of 14,500.

Perhaps some of the dye leeched over to the Wolfpack as well, a possible explanation for why backs from both teams fumbled the ball five times in the game’s first six plays. Four of those went for turnovers.

Carolina scored in the first half after State’s Lawrence McCulley muffed a punt at the 20-yard-line. Five plays later, sophomore quarterback “Slippery Dick” Dashiell hit Charlie Shaffer on an 14-yard touchdown pass. Babe Daniel kicked the extra point that gave the Tar Heel defense, which recorded six shutouts that season, confidence it could hold on for the win.

Both teams threatened in the second quarter, with State losing the ball on downs inside the Tar Heel 20 and Carolina having a touchdown run called back because of a penalty. The threat ended when defensive back Venice Ferrar intercepted a Dashiell pass inside the 10. Just before the half, the Heels were again stopped inside the 10-yard-line by State’s inspired defense.

Late in the third quarter, State downed a punt on Carolina’s 49-yard line. Ferrar threw a 24-yard pass to Ray Bardes. Two plays later, Ferrar called a reverse in which he wiggled 24 yards through the Tar Heel defense for a touchdown that stunned the crowd.

Sophomore guard Alex “Bull” Regdon, future Southern Conference boxing champion, came out to make his first extra-point attempt in a varsity game, replacing veteran captain Charlie Stanko. Despite a heavy rush, the young kicker booted the ball straight through the uprights to tie the score in the rivalry game.

The Wolfpack did not win another game in Anderson’s inaugural season to finish 2-6-1, and the Tar Heels did not lose again for Snavely to finish 7-1-1.

After the season, Snavely confided to some friends back in Pennsylvania, where he was recruiting with assistant coach Lefty James and on their way to see the annual Army-Navy game, the dye poisoning was the cause of the disappointing outcome. He didn’t know one of them was a writer for the Harrisburg Patriot newspaper and the following comments caused quite a stir back in North Carolina.

“Our boys just couldn’t give it their best that day, despite the fact that State was probably the weakest team we had played this season, and the result was that our club, considered much better by the experts, was held to a tie,” Snavely told what he thought was a confidential audience. “Doctors said none of the players would suffer any serious results by playing except that their wind would be cut and they would probably have a hard time keeping up with the action.

“And that’s exactly what happened.” Snavely said.

Back in North Carolina, the newspapers had a bit of a field day with the self-inflicted poisoning excuse and Snavely quickly backtracked.

“Those quotations by the Harrisburg writer do not express my sentiments or belief, and certainly they are not fair to Coach Hunk Anderson of State,” said Snavely as he returned from watching the Rose Bowl in California. “I wouldn’t blame Hunk if he resented such statements. As a matter of fact, I think the State team played a fine game that day against us and it capitalized on the opportunities which its fine play made.”

“I think State’s game against us showed some mighty fine coaching. Hunk had seen us play other teams using the Notre Dame system, and he was smart enough to arrange a style of offensive play, which would avail best against our defense, and a style of defense which would do best against our offense.”

The next season, the Tar Heels went 8-1, missing a chance to become the first team from the Old North State to play in the Rose Bowl when it lost the season finale to Duke. He then left to become the head coach at Cornell for nine seasons, before returning to Chapel Hill in 1946 just in time to bring in World War II veteran Charlie “Choo Choo” Justice, two-time runner up in the Heisman Trophy race, and take Carolina twice lose in the Sugar Bowl (1947, ’49) and to lose in the Cotton Bowl Classic (1950).

After three consecutive losing seasons, he was fired, finishing his career at Washington University in St. Louis. He was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1965.

Tim Peeler is a regular contributor to The Wolfpacker and can be reached at [email protected].