Tim Peeler: NC State's role in Duke's 1942 Rose Bowl

There has never been a bigger game or event at Duke Stadium than the 1942 Rose Bowl.

Long before the Durham school named its iconic stadium — where NC State will play the Blue Devils Saturday at 8 p.m .— after its most successful coach, Wallace Wade, it had the means and opportunity to host “The Granddaddy of Them All.”

The city of Durham and its 60,000 inhabitants organized a massive undertaking with just 15 days’ notice in the aftermath of the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. It had lots of help, including from its neighboring rivals at NC State, North Carolina, Wake Forest and Davidson.

Durham was hardly a tiny hamlet on the fringes of Duke Forest, but it still needed plenty of help when the just-announced matchup between No. 2 Duke and Pac-10 champion Oregon State was canceled by the U.S. War Department, which banned outdoor gatherings of any size on the West Coast, beginning after the Dec. 8 declaration of war. Durham offered to host the game, with the approval of the government and the Tournament of Roses Committee, which were easily two of the most powerful entities in the country at the time.

Because of the tobacco industry, textile manufacturing, an active civil rights movement and the establishment of the $40 million Duke Endowment that changed the name of Trinity College to Duke University, Durham was one of the most thriving cities in the state just prior to World War II. While it lost about 10,000 residents during the Great Depression, 1940 census data put Durham as the state’s third largest city (60,200), behind Charlotte (100,900) and Winston-Salem (79,800). Raleigh (46,900) was well behind, smaller at the time than Asheville (51,300), and Chapel Hill, Wake Forest and Davidson were mostly just college towns.

All of them, however, were needed to plan the first big national sporting event in Old North State history, when the annual California postseason game picked up everything except the Tournament of Roses Queen and brought it to North Carolina.

Both NC State and North Carolina offered opposing team Oregon State their athletics facilities for training, and Raleigh’s Sir Walter Hotel and Chapel Hill’s Carolina Inn offered accommodations. The Beavers stayed in Durham, but had three days of locked-down practices at UNC’s Kenan Stadium.

NC State loaned Duke its sports publicist, Dick Herbert, to his alma mater. Herbert, who later became the sports editor of the News & Observer and basketball sycophant to NC State’s Everett Case, went to California to help with the logistics of getting Duke to Pasadena and was working on that very thing when the U.S. War Department forced the Rose Bowl’s cancellation because of national security concerns.

He was there on Dec. 15 when the Tournament of Roses committee, with War Department approval, agreed to move the game to Durham.

Similarly, Duke borrowed UNC assistant athletics director Bo Shepard to help make travel and game-day arrangements.

On the day of the game, Herbert was in charge of Duke Stadium’s press box, which was, in reality, the president’s box for special guests. Herbert kicked out North Carolina Governor Melville Broughton and his wife, University of North Carolina System president Frank Porter Graham, his future boss and News & Observer publisher Josephus Daniels and Tournament of Roses Committee president Bob McCurdy, sending them out to the sold-out stands. They spent the entire game sitting in a chilly January rain. (No one knew how to dress for the game. Newspaper reports said it was going to be sunny, but that was just a guess. The U.S. government would not allow a weather report to be released until Dec. 31, citing security concerns.)

A former NC State football and basketball coach, Gus Tebell, had a huge impact on the game. The Indiana native and four-sport star at Wisconsin was one of four game officials, serving as the referee. At the time, Tebell was Virginia’s basketball and baseball coach.

Since Duke Stadium held only 35,000 spectators and more than 54,000 tickets were sold before the game was even moved — including 271 to Hollywood actor Bing Crosby — there was a huge need for bleacher seats to be added to the upper concourses. NC State, North Carolina and Wake Forest trucked grandstands from Riddick, Kenan and Grove stadiums to Durham to expand seating.

With so many people and no alcohol allowed in the stadium, they needed entertainment throughout the game. Duke invited the full lineup of performers from NC State, North Carolina and Davidson to create a 300-piece marching band and generate some energy on a dreary day.

It was all part of the lively week of activities for both teams, in which the whole state soaked the visitors from Oregon with Southern hospitality. Oregon State was treated to a Christmas dinner of country ham and sweet potatoes, along with a mid-week feast of barbecue and Brunswick stew at Josh Turnage’s Durham restaurant. They spent a day in Pinehurst, with some players and coaches on the golf course and others watching a polo match between teams from the Village of Pinehurst and Fort Bragg.

Players got plug chewing tobacco, handmade cigarettes, Durham-woven women’s nylons and men’s socks as bowl gifts.

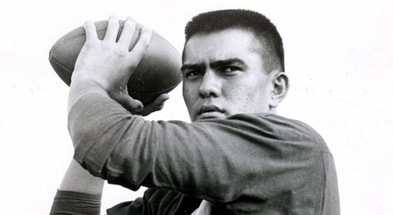

Perhaps the biggest contributor from NC State was a member of the Wolfpack football team, Dashing Dick Watts, a running back from Baldwin, New York.

The Wolfpack hosted Duke at Riddick Stadium in the unbeaten Blue Devils’ season finale on Nov. 22. Duke won 55-6 and Watts, a senior who had earned All-State honors for two consecutive years, did nothing of note, just like coach Doc Newton’s team that season, which ended with a 4-5-2 record.

“It wasn’t a great football club, but who wants to watch a team that wins all its games anyway, is always superior?” wrote the 1942 Agromeck. “In competition, there is spice.”

When the decision was made to play the game in Durham, Wade was bound and determined to have the best-prepared team on the field.

He put together what has been called “the most talented scout team in the country,” bringing Chicago Bears triple-threat quarterback George McAfee back to Durham to run the Blue Devils scout squad and mimic Oregon State’s offense. McAfee, a lefthanded passer and kicker, was similar enough to Oregon State’s Donald Durdan to run against Duke’s dominating defense. Another Duke grad on the scout squad, Jasper Davis, had played for Wade’s 1938 Rose Bowl team.

Watts, a four-sport star for the Wolfpack, was just getting a little extra time in the college football spotlight, pretending to be a Beaver running back, before joining State’s track, baseball and boxing teams. After Rose Bowl practices were over, he returned to NC State to finish his studies and join the Wolfpack football coaching staff as a graduate assistant for 1942 spring practice.

After graduating with a degree in textile weaving and designing, he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps for flight training and ended up serving as a pilot during World War II. He continued his career in the Air Force and retired after reaching the rank of colonel.

Watts died in California in 1988, one of the last NC State connections to Durham’s greatest event.