Why are U.S. Senators introducing bill targeting 501(c)(3) NIL collectives?

For months, people operating in the NIL world have been debating whether or not collectives that have received 501(c)(3) status from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) are truly public charities and if donations to the groups should be tax-deductible.

Outside of “pay-for-play” implications in recruiting, the question of whether a collective can actually be a charity has been the most widely debated topic by NIL experts.

Collectives are groups of boosters that pool funds from a wide swath of donations to help create NIL deals for student-athletes. There are currently more than 160 publicly known collectives with many of the most ambitious in the country receiving 501(c)(3) status.

It’s become such a hot-button topic that U.S. Sens. John Thune (R-SD) and Ben Cardin (D-MD) introduced a new piece of NIL legislation on Wednesday.

Both sit on the Subcommittee on Taxation and IRS Oversight. Their bipartisan legislation prohibits individuals and organizations – NIL collectives – from using the charity tax deduction for contributions to compensate collegiate athletes in the NIL space.

Titled the Athlete Opportunity and Taxpayer Integrity Act, it is aimed specifically at collectives that have claimed 501(c)(3) status. Universities would be exempt from this legislation. The bill also financially encourages would-be donors to give money to athletic department-run collectives.

So, why is there such a debate about collectives with 501(c)(3) status? Much like anything with the IRS, tax law and NIL in general, the answers are complicated.

What exactly does 501(c)(3) status mean?

Ryan Whelpley, an associate in the Corporate Practice Group at Morse in Waltham, Mass., has written extensively about the tax consequences surrounding NIL deals.

Whelpley told On3 that 501(c)(3) is a reference to the section of the IRS code that allows for the tax exemption of certain organizations, commonly known as charitable organizations. Whelpley said there are around 30 different types of 501(c) organizations, but 501(c)(3) is the most common type.

To be designed as a charitable organization, Whelpley said groups have to file Form 1023 – a 12-page document – that outlines the charity’s structure and formally applies for recognition of exemption under the IRS code.

“I believe on the IRS’s website it says it receives more than 95,000 applications each year,” Whelpley said. “That’s a high volume for them to sort through, especially with them going through COVID. The timeframe for these varies widely. Pre-COIVD, the average processing time was three to six months. Post-COVID and currently, the timeframe for processing is nine to 12 months.”

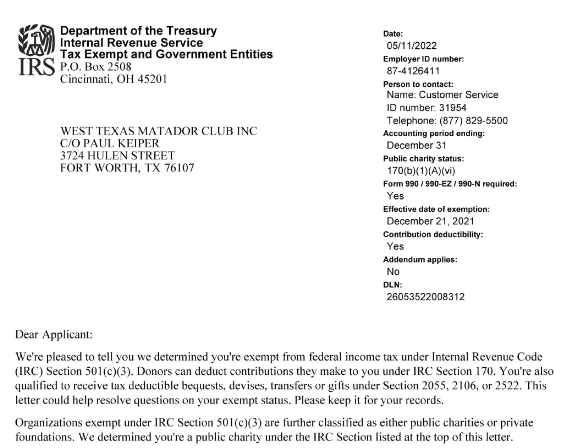

What do letters from the IRS say?

On3 reviewed the determination letter of more than a dozen collectives that were granted tax-exempt status. Every one of them was designated by the IRS as a public charity.

“We’re pleased to tell you we determined you’re exempt from federal income tax under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 501(c)(3),” the letters On3 reviewed said. “Donors can deduct contributions they made to you under IRC Section 170… Organizations exempt under IRC Section 501(c)(3) are further classified as either public charities or private foundations. We determined you’re a public charity under IRC Section listed at the top of this letter.”

Additionally, Whelpley said one of the most notable differences between for-profit and nonprofit entities is how their organizers obtain capital to run their businesses.

For-profit corporations can use their own money or earned profits or seek investment funds from private investors. Investors expect a return on their investment, which motivates for-profit corporations to succeed.

By contrast, nonprofit corporations seek donations, rather than asking individuals or corporations to invest in their businesses.

Rather than expecting equity or financial gains from nonprofit businesses, donors expect a “social return” on the money they invest. In fact, the 501(c)(3) statute specifically states that no private or individual shareholder may benefit from the organization’s earnings.

Another big differentiator is the purpose, Whelpley said.

“Nonprofits have to have an exempt purpose to qualify for 501(c)(3) status, such as a charitable purpose,” he said. “Whereas, a for-profit business’ purpose is not limited to exempt purposes such as charity, religion, education or scientific.”

Can NIL collectives be charities?

The answer to the question of how NIL collectives can be designed as public charities and donations written off is also complex.

Katie Davis, a practice lead for higher education and collegiate athletics at CPA firm James Moore & Co., recently told On3 that how a collective is operating is one of the key things to consider when answering that question.

“Step one is getting approval from the IRS,” Davis said. “But then, they’re watching and monitoring. You have to go through annual reporting to say, ‘Yes, OK, I am actually operating with a charitable intent.’

“The IRS also has a certain public support test. You have to get support from the public. It can’t just be concentrated on a handful of individuals. For the purposes of this calculation, even the people that give large sums, those large sums could be limited for purposes of the calculation when you’re looking at the total.

“My thought is that eventually, it could become pretty challenging for some of these NIL collectives to pass the public support test. They’re going to be a handful of large donors – potentially – unless there is some larger grassroots type campaign and fundraising that’s going to support the collective.”

Yet, Davis said all nonprofits are given five years to meet the public support test and the calculations are on a five-year rolling average. And in today’s fast-forward world of NIL, five years is an eternity.

That’s why Davis said collectives deemed charities can be better judged on what’s the public perception of how the group is operating. Plus, whether or not the IRS agrees with the operations compared to the organization’s mission statement is critical.

“Are you operating in accordance with your mission?” Davis said. “How does the public feel about that? Some mission statements are pretty vague – ‘educational opportunities, etc., etc.’ I think that’s questionable if athletes are receiving large sums of money to sign autographs at a nonprofit.

“But there could be collectives that are set up right that could truly have a charitable purpose. If they’re looking at appearances or the student-athletes actually rolling up their sleeves. So, you want to make sure that there’s a charitable purpose for the money that’s being spent. Otherwise, it’s possible that they could jeopardize their status as a public charity.”

‘Somebody will go to jail’

That blurred line between collectives that have student-athletes doing actual charitable work and others that say they do but are just using it as a way to maintain their roster through “salaries” is what concerns many.

Mit Winter, a sports attorney at Kennyhertz Perry LLC and one of the most influential voices in the NIL space, is one that is concerned.

“To me, it’s not clear that the way a lot of these collectives that are currently 501(c)(3)s are operating is for a charitable purpose,” Winter said. “To maintain their 501(c)(3) status, they’re going to have to show ‘Here’s our mission. Here’s how our operation is, and paying these athletes is actually serving this mission.’ So, I think a lot of 501(c)(3)’s mission really doesn’t match up with the way they’re operating. That could create big problems if the IRS audits them.”

Jason Belzer, CEO of Student Athlete NIL, which manages the day-to-day operations of several successful collectives across the country, said it’s good to have a 501(c)(3) arm as the overall part of a collective. But he also believes some that are entirely focused on 501(c)(3) might have malicious intent.

“It’s nice to have that piece, but it’s a small piece of the pie,” Belzer said, while also pointing out that there’s a cap on what student-athletes can earn for doing charitable work and they must be paid fair-market value.

“Many of these collectives that have popped up with a mission of 501(c)(3)s are simply looking for a way to launder money. They think they can get around the IRS. Somebody will go to jail for wire fraud because they think they are going to be able to get around the rules of what the IRS is trying to do. Great, you have a 501(c)(3) designation. But it doesn’t suddenly give you the opportunity to pay a student-athlete $100,000 and you give somebody a tax deduction on it.”

Cardin, who has been in the U.S. Senate since 2006, is concerned, too.

“In this new NIL era, we want to ensure that the opportunities available for student-athletes to benefit from their own Name, Image and Likeness are protected,” Cardin said in a news release. “We also have an obligation to protect taxpayer funds, which means that charitable deductions should be reserved for charitable activities. Purposefully blurring the line between private expenses and charitable contributions dilutes both these efforts.”

501(c)(3) collectives can work if done right

Winter says there is a way collectives can operate within the 501(c)(3) world, especially if the groups are paying the student-athletes for work that is serving a charitable purpose. For example, Winter said paying a student-athlete fair-market value to make an appearance on behalf of the charity at a fundraiser would probably “pass muster.”

“But if you’re just paying guys for serving soup, I don’t see how that necessarily aligns with the charitable mission of the collective,” Winter said. “How does that serve the public good by paying to do volunteer work?”

On3 talked with a handful of collective operators currently using the 501(c)(3) model. Almost all of them did not want to speak on the record, but all of them insisted they are staying true to their charitable mission and doing things legitimately.

But many, such as Joe Petsick, an advisor to The Big Red Collaborative, a recently launched Nebraska-focused 501(c)(3) collective, understand the concern.

Petsick said collectives’ leaders must educate student-athletes about what they’re signing up to be a part of. The players need to know it’s not going to be a quick payday like other NIL deals.

“They must understand there will be a number of things we ask them to do on an ongoing basis for these nonprofits,” Petsick said. “We’ll be synchronizing our calendars with the nonprofits. Our group is talking to them about the events they have upcoming. We’ll be working with the promotional stuff they’ll be doing and the visibility they hope to get.

“These student-athletes will be tasked with a number of things to do to remain active and involved. I think that’s different than what has some people concerned. It’s something that I don’t think it’s discussed enough when people start up this model of collective. It’s a process if you’re doing it the right way.”

Legislation could limit student-athletes’ ability to do good

Other leaders of 501(c)(3) collectives say the introduced legislation would limit the impact student-athletes can have on their communities.

Some point to the diverse groups they’ve supported, such as YMCAs, Big Brothers Big Sisters groups, cancer research and programs focused on ending gun violence. Without 501(c)(3) collectives helping bring awareness through star college athletes, some say the charities they support will lose much-needed money that’s generated through fundraising.

“We wanted to have the charitable aspect as part of our foundation,” said Brian Schottenstein, co-founder of The Foundation, an Ohio State-focused collective. “That’s part of the reason I started this… We’re going to continue to fight for student-athletes and our charities and keep pushing our brand forward.”

Winter said the proposed legislation would have a big impact on the NIL world.

“If this bill is passed, it would change things a lot,” Winter said. “There’d be no reason to operate a nonprofit collective.”

Where NIL legislation goes from here?

The last few months have marked a busy time for NIL legislation to be introduced on Capitol Hill. Wednesday’s announcement is the fourth piece to be introduced in the last two months.

Five senators announced plans to reintroduce the Athlete Bill of Rights in Congress, led by Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT). Their bill includes health, wellness and safety standards.

U.S. Senators Tommy Tuberville (R-AL) and Joe Manchin (D-WV) sent letters to 30 collectives asking for feedback as part of their process of drafting bipartisan, federal legislation related to NIL.

And U.S. Senator Roger Wicker (R-MS) reintroduced a bill aimed at curtailing the impact NIL has made in recruiting earlier this month. Most importantly, the bill prohibits former student-athletes from retroactively suing over NIL. The legislation also states athletes would not be considered employees – the main argument some Republicans and Democrats have had over NIL legislation.

And then there’s the latest piece of legislation, introduced Wednesday, which would curtail tax-deductible collectives.

Where NIL legislation goes from here is a major question. Midterm elections are nearly a month away. Conference commissioners called for reform, driven by legislation, on Capitol Hill throughout the summer. And Democrats and Republicans continue to remain fair apart from on much of the language being introduced in these bills.

The one route, sources say, is that the House of Representatives goes Republican and the party holds control of the Senate following November’s elections. This would allow a window where a piece of NIL legislation could be passed.

On3’s Pete Nakos contributed to this story.